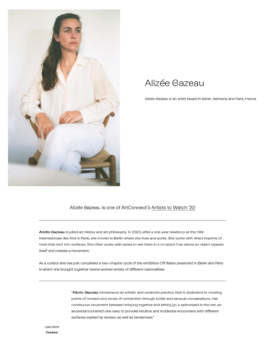

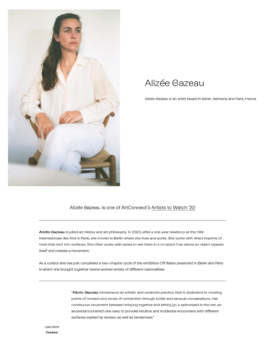

Alizée Gazeau (b. Paris, 1990) lives and works in Berlin. She holds a master's degree in art history from La Sorbonne, where she also studied philosophy of art.

Solo exhibitions include A Shadow’s Shadow, Sainte Anne Gallery, Paris, France (2025), I’m Herdsman of a Flock, Stallmann Galleries, Berlin, Germany (2024), Häutung, Gr_und with the support of the French Institute, Berlin, Germany (2023), Le Filet, Ona Project Room, Tokyo, Japan (2022), Heureux qui comme Ulysse, Bubenberg, Paris (2017).

Recent group exhibitions include Dream Weaving curated by Juliet Kothe and Azza Satti, Ambassade de France, Nairobi, Kenya (2025), Ballad of a runaway horse curated by Paulo Iverno, Paris, France (2025), éternelles errances, Centre Wallonie Bruxelles, Paris, France (2025), Jum Jum Jum, Pill, Seoul, Korea (2024), Mass, Spoiler Zone, Berlin, Germany (2024), H20 Venezia: Diari d’Acqua, Lapis Lazuli: artE with the support of the Fondazione Barovier&Toso, Venice, Italy (2024), Archive of Upcoming, Georg-Knorr Bremse Factory, Berlin, Germany (2023), Art Theorema Krisis, Fondazione Benetton, Trevise, Italy (2023), Off Water II, Sainte Anne Gallery, Paris, France, (2022), Interfaces, or those who caress the surface, Interface, Berlin, Germany (2021), But are we the only dreamed ones? curated by Faidra Vasileiadou, Daily Lazy Project, Athens, Greece (2019).

Alizée Gazeau was resident at the Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France (2019-2020, 2025), at La Chapelle Saint Antoine, Naxos, Greece (2024), at Lapis Lazuli: artE, Venice, Italy (2023), at the Fondation Hartung Bergman, Antibes, France (2018), at the Fondazione Michelangelo Pistoletto, Biella, Italy (2018), at Artemis Studio, Ikaria, Greece (2018) among others.

Between 2018-2022, she founded and edited Publication d'Art Non linéaire, a collective publication of artists and historians, giving rise to several events and conferences, at Musée Pierre Soulages, Rodez, France, at Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France, at Emerige Voltaire, Paris, France.

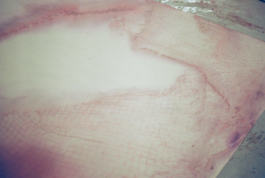

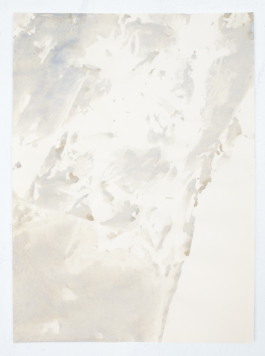

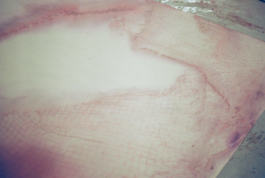

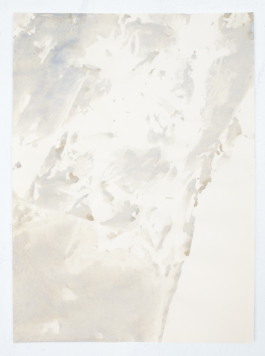

Fragment, 01,01, 2025, acrylic and ink on canvas, 120x90 cm

"A Knot is a Tight Place" written by Mariana Lemos and Mélanie Scheiner for Duets, edited by Mariana Lemos and Gigi Surel, London, June 2025

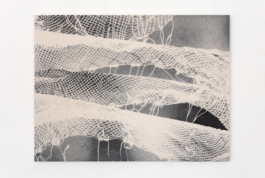

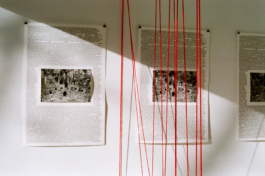

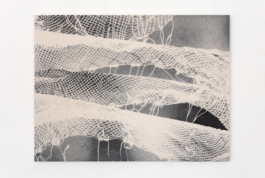

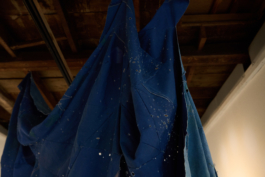

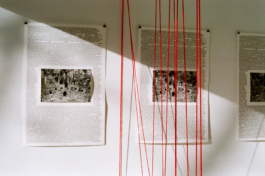

Studio, Nets used for painting, 2025, Berlin

Ballade of a Runaway Horse, a group show curated by Paulo Iverno, Paris, 2025

Sans titre P (worn-out saddle), 2025, horse saddle, approx. 60x80x40 cm & Sans titre (stirrups), 2025, leather, stirrups, variable dimensions

Théâtre National de Toulouse - CDN Occitanie

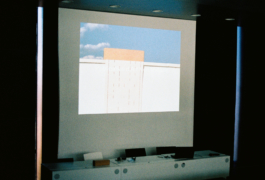

Dry River, 2025, acrylic on cotton canvas, 16m x 5,80m - a painting produced for the stage of Le Rêve d'Elektra by Clément Bondu, 2025

https://theatre-cite.com/programmation/2024-2025/spectacle/le-reve-d-elektra/

A Shadow's Shadow at Sainte Anne Gallery, March 7 - April 26 2025

A SHADOW'S SHADOW

a conversation between Alizée Gazeau and Joséphine Dupuy-Chavanat

Joséphine Dupuy-Chavanat: “ To title is to write a little!” said Alechinsky in 1911. Your first solo show was entitled Heureux qui comme Ulysse [Happy who like Ulysses], evoking the journey and the fragmentation of memory, while your second, Häutung [Molting], explored the idea of metamorphosis and the creative process. Recently, your much more conceptual exhibition I'm Herdsman of a Flock looked at the transformation, permeability and polysemy of familiar objects, particularly those from the marine and equestrian worlds. What motivated the title of this new exhibition at Sainte Anne Gallery?

Alizée Gazeau: A Shadow's Shadow is a quote from Hamlet. The exhibition is the first personal presentation of my paintings and sculptures in Paris after four years living in Berlin. I wanted to compose a series of paintings based on past and recent sensations, like the cast shadows of memory. Shadows come with light. The shadow of a shadow is two lights on objects that project onto each other. I like the idea of repetition, of the same word, the same motif, like a rhythm, a poem, a dance. A little further on, Shakespeare writes 'a dream itself is but a shadow'. In the paintings, we recognize the object of the net, the hammock, but as in a dream, it is no longer exactly the object, nor its abstraction. Three ensembles of sculptures punctuate the exhibition. They follow on from the horse saddle sculptures exhibited in November at Stallmann Galleries in Berlin.

So there's a fluidity, a kind of interstice that you constantly capture in your work. A moment that also seems suspended, between two states. The net, for example, seems to escape us the moment it appears. As for the leather straps, they play on the varying degrees of tension in their braiding, fused at one end and loose at the other. You mentioned recent sensations. Can you tell us what they are and how they may have influenced the paintings and sculptures presented here?

You said that the exhibition of horse saddle sculptures was more conceptual than previous ones. This is true and paradoxical at the same time, because it marks a moment when I have fully assumed the part of sensitive intuition in my work. The horse saddles, the braids made from their girths, the pieces cut from leather are sensual elaborations that respond to a very direct intuition. The net is an object I began collecting in 2019. Instability, loss and the fluctuating memory of a place are translated into painting through this object. Working on the ground, with pigments and water, it becomes a tool that allows me both to hold the paint on the surface of the canvas and to let it escape. There's a tension between letting go and holding back that I like to find in the process. As you say, we find the same tension between the idea of capture and liberation in the leather braids. These archetypal objects are like metaphors.

And what are these metaphors?

The idea of metaphor is that of a displacement from the original object. “Hammocks and fishing nets stem from ancestral practices. The oldest known fishing net in Europe dates from 8300 BC. The net in ancient Egyptian bas-reliefs functioned as a representational screen and can be seen as a metaphor for space and time.” In my paintings, the nets create spaces and capture events. The horse saddles are metaphors for the search for harmony between two beings, having an asymmetrical relationship. The sculpture Untitled (stirrups) is made of leather straps and stirrups. The stirrups, designed to maintain balance, are aligned vertically on the straps. They evoke a ladder, the axis mundi, that is, the connection between Heaven and Earth. When I speak of metaphor, I am referring to the idea that the work eludes definition, constantly projecting its form onto an infinite number of other thoughts.

I remember you sharing your thoughts with me when I was working on a project involving the graphic interpretation of music. You told me that between the appearance of a form and its disappearance, there exists a fragile compositional equilibrium. And painting - like music - seeks harmony. How does this quest for harmony, a subject that has long been dear to you, continue to infuse your work? I say “quest”, but perhaps you have found the right melody, the right rhythmic flow and the perfect consonance?

Yes, the word harmony was a recurrent theme. Music provokes instant emotions. I would like my paintings to be listened to and my sculptures to be perceived as a rhythm. This may sound abstract, but at the same time it is concrete in my works. Shapes appear as much as they vanish. I like them to produce a temporal, musical impression, something both anchored and fleeting. In the First Dance and Movement paintings, I searched for a perfect balance between light and darkness, a point of equilibrium between two opposites.

“The ocean is deathless - The island rise and die - Quietly come, quietly go - A silent swaying breath” Agnes Martin

I'm also thinking of Roni Horn, Sigmar Polke and Eva Hesse.

I do indeed remember the Sigmar Polke exhibition at Palazzo Grassi in Venice, which described the artist as “the painter of metaphors”. One of the huge works on show featured circus characters and animals balanced on chairs, buckets and ladders. Polke transforms and even metamorphoses his colors, like an alchemist. How do you work with materials and colors? Do you, like Polke, seek to create - through a singular use of pigments - a state akin to hypnosis?

I began imagining the paintings for the exhibition during a few weeks spent away from my studio. As always in my work process, I need to immerse myself in places, readings, conversations and emotions to prepare a new series. Back in the studio, a blending occurs between my intentions and the interactions that take place between pigments, paint, water, threads and the surface of the canvas. The paintings from the Surface series are made with a single color. I compose the painting by placing water-soaked nets on the canvas. By moving the pigments, the nets modify the pictorial surface, and after they are removed once dry the final painting appears. In this, I am also a kind of alchemist. There are certain colors that come up frequently: the contrast of black and white that structures the nets, the crimson color of bodily flows, of the sea in the Odyssey, of vital momentum. In the painting Suite, the fleeting shape of the net was almost enough on its own. I wanted to add a blue line to indicate temporality and movement. There is also the imprint of a net that traces a very low horizon line. You speak of a state close to hypnosis. What is certain is that I am led by my intuition, by the fluctuations of my memory and by the beauty of the absolute present offered by a painting in the making.

éternelles errances, curated by Marianna de Marzi, organized by Culturfoundry and les amis du NMWA, Centre Wallonie Bruxelles, Paris, 2025

Monopol, Interview Lina Stallmann with Hilda Dirks, 2025

"Davor, dahinter und immer weiter" by Beate Scheder for Die Tageszeitung, 17.12.2024

https://taz.de/Die-Kunst-der-Woche/!6054337/

I'm Herdsman of a Flock at Stallmann Galleries, November 24th - January 31st, 2025

Opening November 23rd 4-8pm

Jum, Jum, Jum, Orbit, curated by Rio Usui, at Plli, Seoul, photos Bokyoung Han

Residency at La Chapelle Saint Antoine, July 2024, Naxos, Greece

Bureau des arts plastiques, Institut Français de Berlin

Alix Weidner

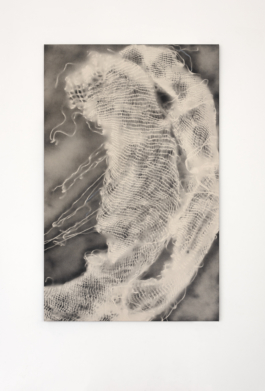

From her studio in Berlin-Neukölln, Alizée Gazeau introduced us to her work on materiality. Based in Berlin for the past four years, the artist’s practice is mainly pictorial, but also includes installations. She is interested in intermediate surfaces that, like a fishing net or a glass float, lie between elements such as air and water. Other objects, such as a leather riding saddle or wooden tiles, stand between bodies and species, but also between bodies and spaces, and give food for thought about the contact surfaces that surround us and their permeability. For Alizée Gazeau, these objects are powerful points of interconnection, holding back or separating materials but also connecting entities. They give rise to rubbing and friction that, when fixed by paint on larges canvas or activated in installations, result in new symbiotic, organic and even dreamlike forms.

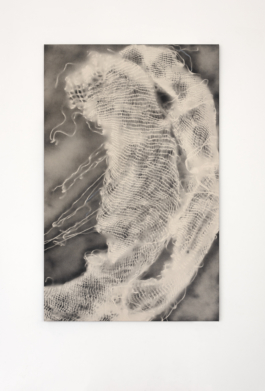

Alizée Gazeau’s pictorial work is at the same time restricted to a two-tone palette, while multiplying the effects of nuance and transparency on large imposing formats. She told us about her interest in the sea, which led her from the French Atlantic coast to the Venetian Lagoon, for water’s ability to penetrate substances and offer infinite interplays of tones and light. While her latest black-and-white pieces take up these forms of aqueous fluidity, they are also reminiscent of the photogram image. This photographic technique consists in placing objects on photosensitive paper to capture their direct form, giving both a formal or abstract rendering and, at the same time, a direct transcription of the objects used, i.e. an imprint of reality. This duality is reflected in the paintings of Alizée Gazeau, whose serial work cultivates and masters trouble from canvas to canvas.

MASS, group show at Spoiler Zone, Berlin, 2024

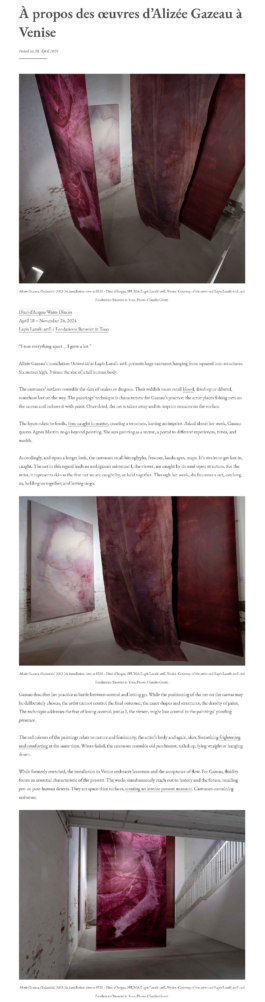

À propos des oeuvres d'Alizée Gazeau à Venise

Review by Christina-Marie Lümen, 2024

https://cmarthoughts.com/alizee-gazeau-lapis-lazuli-arte-venise/

H2O Venezia: Diari d'Acqua

text of the exhibition written by Laure Martin-Poulet, catalogue, Venice, 2024

H2O Venezia: Diari d'acqua

WATER AS A COMMON THREAD IN THE WORK OF ALIZÉE GAZEAU

text written by Laure Martin-Poulet

(...) Alizée Gazeau develops in this way a poetic and meditative body of work, leaving ample room for experimentation and for chance. She seeks to offer the viewer the freedom of an appropriation, a personal immersion, based on the following postulation: ‘When the work enters into an exhibition space, it does not belong to me anymore, it is not about me anymore – the work has to speak for itself’ (interview with the artist by Lisa Deml, Berlin, January 2023). With this, Alizée Gazeau echoes the credo of Louise Bourgeois, who belongs to her personal pantheon of artists alongside Agnes Martin: ‘A work of art has nothing to do with the artist, a work of art has to stand by itself’ (Louise Bourgeois, ‘Destruction of the Father. Reconstruction of the Father’, 1998, p.168).

From the start, she approaches the question of landscape in painting and drawing through the bias of abstraction and metaphor. In 2016, in her very first series of works, aptly entitled ‘Incipit’, Alizée Gazeau adopted the technique of collage, which she appreciates for the freedom it entails. Using as backgrounds old, very classic seascapes dating back to her classes at Ivry, upon which she arranged shapes cut from silk paper, she composes a fragmented landscape, seemingly shattered. Exploring the question of horizon, of the island as an imaginary utopian place, she created, during a trip to Cuba in 2016, a series of collages titled ‘Lines and Forms on Cuban Walls’. Upon her return, the reading of Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, inspired a new series of collages presented in her first solo exhibition, in October 2017 at Bubenberg Gallery in Paris, with the title ‘Heureux qui comme Ulysse’ (Happy who like Ulysses). From Homer’s story, she extracted words that she transposed into coloured figures on fabric, affixed to the canvas, forming an archipelago of sorts. Earlier that same year, during a stay at La Baule, Alizée Gazeau created ‘Silence and Noise’, a work composed of a glass plate with collages of abstract silk paper shapes, yet again evoking the idea of islands, and a frame on which hangs white silk gauze. She made it the subject of an ins- tallation-performance, of which she has preserved the memory in a series of black and white photographs. On the beach, Alizée Gazeau moved the glass plate, and the shadows of the collages were cast onto the silk sail attached to the frame planted in the sand. This was an important moment, which she remembers: ‘For the first time, I felt I could trust my intuition, and escape the convention of painting, the collage’*. This initiatory experience continues in other works, by summoning the action of natural elements, she incorporates the random, the unexpected.

This way, in February 2020 in La Baule, Alizée Gazeau, while seeking out an idea for an invitation card, made a cyanotype of a fishing net, which she printed on canvas, before affixing it to a salvaged wooden pallet and placing it at the water’s edge to photograph it. The waves suddenly swept away the work, transforming it into a raft adrift, like the aftermath of a shipwreck. On the spot, she transformed this incident into an improvised performance, capturing it in a series of photographs titled ‘If a clod be washed away by the sea (after John Donne)’. In an unsettling coincidence, just a few weeks later, the Covid pandemic upended the entire world.

But let us return to spring 2018, when a significant turning point occurred on the occasion of a first artist residency on the island of Ikaria in the Aegean Sea: the transition from collage to imprint. Embracing this ancestral technique, the artist made there her very first imprints with cotton fabrics soaked in pigments collected on site and mixed with acrylic and water from the river Halaris, which gives the series its name. She continued in this new direction with other works made by using olive branches, with the title ‘OE_18’. These were made during her residency at the Hartung Bergman Foundation in Antibes in September 2018, where Alizée Gazeau found material for her art in the surrounding nature, a source of inspiration for the work of Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman, with invaluable encouragement and support from Thomas Schlesser.

Continually striving to go beyond the ‘surface of things’* in a fluid gesture involving not only the eye and hand, but the entire body, Alizée Gazeau explores new practices and materials, while remaining in the register of abstraction, which grows in corporality without losing its lyricism.

In 2019, the discovery of an abandoned fishing net in Le Croisic reminded her of the drawings made in preparation for the first edition of the journal PAN, ‘Horizons’, in 2018, in which she attempted to transcribe the concepts of rhizome and immanence set forth by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. This modest everyday object, emblematic of the maritime world, becomes her paintbrush as well as an old hammock made of braided rope. Since then, she has begun creating different series of paintings in ever-larger formats, skillfully balanced between control and letting go. The process is always the same for all of them: she plunges a net or hammock into a first bassin of water and acrylic paint before placing it on the surface of the canvas on the studio floor, moving it around, then letting it dry and removing the net or hammock. She enjoys this ‘moment of revelation, which is always a surprise’*. Sometimes she starts again, using the same process, adding one or more extra layers until she is satisfied with the result, as testified by some of her paintings from the series ‘SH_23’ from 2023.

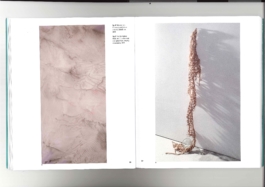

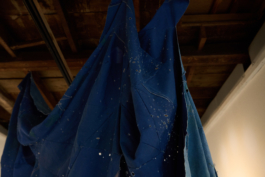

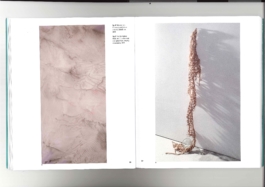

More recently, alongside painting, she started exploring the field of installation and sculpture. In a solo exhibition in Tokyo in 2022, she presented ‘Untitled (Boat cover)’, a piece made in 2020 using an old family cotton boat cover, cut into diamond shapes and sewn back together. Hung from light wooden structures with the light passing through moth holes, this canvas takes on the appearance of a map of the stars. In January 2023, in her exhibition ‘Häutung’ (moulting) at Gr_und gallery in Berlin, where she now lives and works, she showed ‘Phaethon’, a sculpture from 2022, composed of a horse saddle and a cotton sail also sewn from diamond-shaped pieces. With an unprecedented sexual connotation, this work offers a striking contrast to the large monochrome imprint paintings from 2022 that fill most of the space.

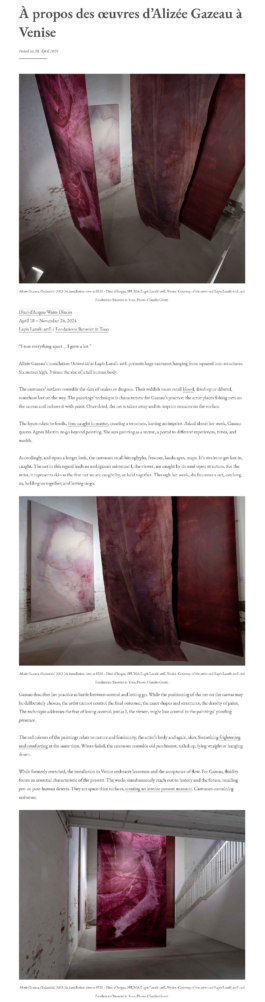

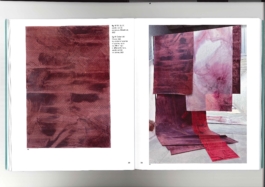

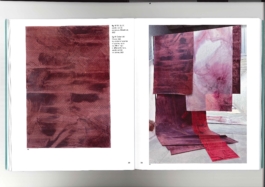

In Venice, where water is omnipresent, she feels in her element. On the occasion of the 60th Biennale, Alizée Gazeau is exhibiting a series of acrylic and ink paintings on canvas in shades of red, made during her residency organised by Lapis Lazuli: artE, an art consulting firm that has been promoting young artists since 2023. She

is presenting it as an installation titled ‘Océanicité’. While the term (Oceanicity) references the degree to which the climate is influenced by the sea, for the artist it has a more personal and more ambitious dimension: ‘I have associated this climatic concept with a more intimate concept, that of empathy. The degree to which an individual is affected by the environment, how my interactions in the world, my encounters, my exchanges affect my emotions as well as my paintings. Red is the colour of life, it is an organic, vibrating colour, I wanted to create a series of works where the viewer would have a sense of diving beneath the surface’*. Additionally, in keeping with the broadening of her field of artistic production, she is presenting two sculptures, of which one of the constituent elements, old glass floats used for fishing, again alludes to the maritime world. Here is what Alizée Gazeau says of them: ‘Freed from the mesh, they gain a highly feminine appearance. I brought them with me to the Lido, I spent an afternoon throwing them into the sea and fetching them back from the waves. Charged up from this performative moment, archived in a series of film photos, I brought them back to the studio where I had the idea to construct nets and create sculptures made from the assembly of these two objects. I cut from the cotton canvas thin strips of fabric that I tied together to make small nets, in which these glass balls are hung. One of these sculptures pays tribute to one of my favourite sculptures by Eva Hesse, ‘Ohne Titel’, from 1966*.

Alizée Gazeau’s work unfolds in successive waves, in a tireless quest for new expressive horizons. With persistent humility, she relentlessly explores and reinvents herself in a form of continuity, taking risks; this is the mark of a true artist.

*: quotations from an interview with the author and the artist in Paris on 22 December 2023

H2O Venezia: Diari d'Acqua

A correspondence of letters with Liberty Adrien, catalogue, Venice, 2024

Berlin, Tuesday 16 January 2024

Dear Liberty,

I wanted to tell you about my outing on the Lagoon on 2 October 2023. I met Pietro Consolandi at Piazza Santa Maria Elisabetta on the Lido to take a boat ride. The horizon widened. The Lagoon stretched from barena to barena, and I felt like I was in the heart of an organic archipelago, in the lungs of this whole body that was seeking to reach the ocean. The samphire was red, mingling with heather, and we went along Sant’Erasmo at low tide. I was there, plunged into this thickness of duration that Henri Bergson defines as composed of two parts: our immediate past, and our imminent future. Conscious, therefore, of a memory I had come there to preserve.

Venice, 7 December 2023. In the studio, a series of paintings float, hanging from the mezzanine, made over these past three months in Venice. The paintings are supple, flowing; they flutter as soon as I open the door to go out to the garden. They remind me of a sentence Lisa Robertson wrote in The Baudelaire Fractal, ‘Time in water is pliable’. Time in Venice has unfolded gradually over these past few months, like the current of a stream gradually turning into a torrent. I’m facing the paintings. They are red, purple, pink, wrung from the mesh of the nets I used to paint them. Red is the colour of the pulse of life, and purple, that of the Mediterranean in Homer’s Odyssey, frequently threatening and thus, vinous. The paintings evoke an imminent immersion: they stand like flags, freely, sails enveloping their surfaces like a second skin. The other day, you asked me what part of my work is autobiographical. When I came to Venice, I had the term oceanicity in mind, the degree to which the climate is affected by the influence of the sea. I come from the Atlantic coast, from the French departments of Finistère and Loire-Atlantique. My maternal great-grandfather Ester was an Italian immigrant who worked as a mason. He settled in Brest and married Jeanne, who would become a fabric merchant. My grandmother worked for years with her mother in her fabric shop, Le Dès d’Argent in Brest. We always exchanged a lot about colours, textures, fabric and how to preserve, reinvent, fabricate. Her entire memory has been enshrouded in a thick fog, but just recently, we talked more about colours and did some sewing together. The idea of oceanicity allowed me to question myself about the capacity of streams of memory to spark my creativity and the stories of others, my empathy, like an ocean current. Memory is the imprint of reality on the surface of thought. The imprint, as Georges Didi-Hubermann writes, ‘is firstly a gap that is printed, touching and even ‘impressing’ us, in its distinctive and inaccessible memory of contact’. I think my paintings propose a form of living with change, with the fluctuations of thought. What do you think of the idea of inner landscape?

I’d like to end this letter with another sentence by Lisa Robertson: ‘The distinction between inner and outer worlds was becoming permeable and supple, like a fabric, which is in its very technical constitution both structure and surface’.

Warm regards,

Alizée

Frankfurt, 28 January 2024

Dear Alizée,

‘When they went ashore the animals that took up a land life carried this them a part of the sea in their bodies, a heritage with them passed on to their children and which even today links each land animal with its origin in the ancient sea. Fish, amphibian, and reptile, warm-blooded bird, and mammal – each of us carries in our veins a salty steam in which the elements sodium, potassium and calcium are combined in almost the same proportions as in sea water.’ Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us

In recent days, I have plunged back into Rachel Carson’s book, The Sea Around Us. The first work in a trilogy published in 1951, her words weave together poetry and scientific knowledge in an extraordinary exploration of the ocean’s depths and its history. The writer’s representation of the language of the sea made me think of you, in how your series of paintings could be a fragmentary transposition of this.

The notions of layers, sediments, lights and colours, at the heart of your artistic process and essential components of oceanography, have particular resonance. In her book, Carson explores the ‘vertical migration of the layer’ between surface waters, deep waters and undersea reliefs, ensuring undersea life through ‘a series of delicately adjusted, interlocking relationships’. The verticality and essence of these interactions reflect the ones inherent to your works. The paper spread out on the ground, the fishing net placed upon it, the liquid saturated with colour and minerals enveloping them, and the chemical and physical reactions arising from their interactions – of earth (gravity), air (evaporation) and light (colour change) –form your paintings. Once the water has evaporated, leaving behind its deposits in the nooks of the net, which has been carefully removed, a map of traces and processes remains, a representation of reliefs and histories. ‘The sediments are a sort of epic poem of the earth’, Carson writes. Their nature and their arrangement recount the history of the seas and oceans – they are the imprint of relationships.

In your letter, you touch on associations and attributions of colours, relating to your body of work, your biography and your perception of landscapes. These complex interactions between visual and sensorial impressions influence our ever-changing reception of the colours of the seas and oceans. Our vision is affected by the presence of living bodies, microorganisms, molecules and reliefs, as well as by sunlight, heat, time of day and season. Our senses are stimulated by the emergence of memories, places and moments experienced or known, prompted by this contemplation.

The evocation of your personal and familial ties to Finistère, and your interest for the notion of inner landscape, brought to my mind the North Sea coast, in northern France, where I spent much of my childhood. Its landscape has been shaped by two powerful forces: that of strong tides and ruins from History. Every day, the sea, subjected to the pull of the moon and sun, withdraws, sometimes kilometres, revealing a perpetually changing topography of sand. Its windswept dunes, standing opposite the ‘vast world of sea and sky’, as Carson writes, are marked by the spectral, imposing presence of blockhouses. These concrete buildings, attesting to the German army’s occupation during World War II, hold an immense sense of desolation and violence. They’re slowly sinking into the sandy ground, as though the earth were swallowing them up. The striking forces of the natural world here seem to confront Humanity’s fragility. This was my first reception of deep emotions emanating from a landscape. I’ve gone over wordcount, and the hour is late, so I’ll end my letter with a request: I’m curious to know more about your relationship with the notion of Oceanicity.

Looking forward to hearing back from you soon.

Warmest,

Liberty

Zurich, Wednesday 31 January 2024

Dear Liberty,

I was moved by your letter. The evocation of your childhood memories reminded me of afternoons spent jumping from the top of the blockhouse to roll in the dunes on the beach where I spent every month of July as a child. When I came across the term ‘oceanicity’, I saw it as an occasion for a metaphor to speak of painting, and connect questions of marine ecology with questions of creation. Ocean currents have a vital influence on the climate. Since the 2006 international conference on climatology, the case studies exposed the specific risks that global warming represents for our societies; impacts for the most part relating to water issues. The question of adaptability is central to this relationship. A number of marine species are already drifting further north. I think back to Rachel Carson and her perception of the ocean in 1951. Her idea of sediments writing poems in the ocean depths is powerful. The abyssal trenches are indeed the theatre of permanent cataclysmic events. This is what I put in motion during my months of residency in Venice, preparing the painting installation I’ll be presenting in April. I asked myself the question of my place in this uninterrupted current (time and memory), and of the relationship I nurture with my environment (space and surface). My paintings reproduce aquatic movements, they offer a sensuous approach to the surface and speak of capture, immersion and liberation. When I plunge the nets into water and wring them out, when I put them in motion on the canvas, I have a sense of lessening the distances between me and my environment. It’s no longer about contemplating a landscape, a sublime experience in the face of cataclysm. I’m in the paint, plunged into the water, the pigments, the acrylic, the nets. When everything finally stills into an imprint, the painting becomes an archive that has recorded the influence of the movements of the nets. You write it in your letter; what’s beautiful is the continuous rhythm of the tides, the sensation of a boundless immensity, the perpetuation of the space-time continuum. The growing threat of a breach to this rhythm is more worrying than ever. Oceanicity, the degree to which the climate is affected by the influence of the sea. I’ve attempted to confront myself with this degree using my artistic intuition, to preserve the interactions of my body with the movements of the water, through painting.

We’ll see each other in Venice in April. I will be delighted to share this moment with you, for the opening of the exhibition H20 Venezia: Diari d’acqua, at Spuma on the Giudecca.

Warm regards,

Alizée

"Venezia d'acqua e di Impronte", Giacomo Giossi, Il Foglio, April 2024

H2O: Venezia Diari d'Acqua

Lapis Lazuli:artE in collaboration with Fondazione Barovier&Toso

curated by Mara Hofmann, Venice, 2024

H2O Venezia: Diari d'acqua

CROSSING WATERS, CROSSING TIME: REFUGE, ENCOUNTER AND ARTISTIC INNOVATION IN THE VENITIAN LAGOON

text written by Jennifer Sliwka

Venice was born from the lagoon and its islands as a city of refugees. Indeed, as nearby settlements suffered from continuous invasions by Germanic and Hun tribes over the course of the sixth century, their inhabitants fled to the relative safety of the Venetian Lagoon. These diverse groups of immigrants subsequently united to found a city which would ultimately encompass around 118 islands, separated either by expanses of open water or by canals linked by hundreds of bridges. This distinctive context creates the sensation of a city in a constant state of flux, alternately concealed or revealed by the rising or lowering of the tide, the density of the fog and the reflection or diffusion of light. Venice’s watery makeup has long defined its identity, making it both host to, and reliant on, travel and trade. As an island and a port, Venice has always been a natural meeting place for people from different cultures, practices and beliefs and for the exchange of goods and ideas. By the thirteenth century, the city had also grown into a major financial and commercial centre. Together, all of these factors created an especially fertile ground for artistic development and innovation.

Due to its nature as a port city, Venice developed strong trading networks across Asia, Africa and the Middle East so that some of the most prized spices, materials and, especially, artist’s pigments in the world arrived in Venice before making their way through trade routes across the rest of Europe. For example, the semi-precious stone Lapis Lazuli, that vivid blue so prized by medieval and Renaissance artists, was imported by Italian traders during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries from mines in a region that is now part of Afghanistan. The Italians called the valuable pigment ultramarinus in Latin in reference to its provenance from ‘beyond the sea’. Using these minerals and pigments, Venetian artists developed a distinctive style of painting characterized by deep, rich colour (colorito) and an emphasis on pattern and surface. The particular light conditions of the city, ranging from foggy and diffused to bright watery reflections also encouraged a strong artistic interest in capturing these effects. Meanwhile, Venice’s developing shipbuilding industry began using vast quantities of canvas sails, a medium that was swiftly adopted by Venetian painters as a support, a lighter, cheaper and larger alternative to painting on wood panel.

To this day, Venice houses some of the most lauded monuments and artworks in the history of art. The breadth of these works ranges from shimmering gold Byzantine mosaics in Saint Mark’s Basilica to large multi- panelled altarpieces by the Bellini and Vivarini families of painters and from the marble church facades and tomb monuments carved by the Lombardo (Solaro) family of sculptors and architects to the energetic canvases painted by Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese. The majority of these works were commissioned by churches and scuole (religious confraternities) and the wealthy families that patronised them, and it is thanks to them that these artists were able to innovate and transform the artistic landscape of the city, making Venice one of the great touchstones of Renaissance art. Accordingly, Venice was, and still is, a deeply religious city. The city has long endorsed another story about its foundation, one associated with the dedication of the first church, San Giacomo, on the Christian Feast of the Annunciation (25 March) in 421. The day commemorates the visit of the archangel Gabriel to Mary in which he revealed to her that even though she was a virgin, she would conceive a son and become the mother of Jesus Christ, the Christian Messiah and Son of God. In Christian terms, the Annunciation marks the beginning of a new era and in promoting the myth of their foundation on this auspicious date, the Venetians clearly sought to suggest a similar moment of transformation with the birth of their city. While the many churches and scuole in Venice still house masterpieces by the most famous of Medieval and Renaissance artists, it is the galleries, museums and pavilions that now showcase, support and foster the work of contemporary artists. The city’s most famous platform for international art is, of course, the Venice Biennale. Established in 1895, the Biennale is now one of the most prestigious cultural institutions in the world and represents the work of artists from over 75 countries. Alongside the Biennale, collateral events and exhibitions colonise its gardens, palaces, courtyards and shops, so that the entire city becomes a living work of art. Owing to its history and its very particular environmental conditions, Venice is a city with a strong and imposing character, but it is also one that changes according to its inhabitants, weather conditions and artists. Then as today, it is both an exhilarating and daunting place to make art. The five artists represented in ‘H2O Venezia: Diari d’acqua / Water Diaries’ have all embraced this opportunity to spend time in the city and to work there with a great awareness of the distinctiveness of the Venetian context, its histories, artistic legacies and particular challenges. Their own experience and practices, however, have been developed in countries around the globe, including France, the Netherlands, Australia, Argentina and China, and this project invites them to look at Venice through their own distinctive lenses. The works in this show offer new interpretations of how the city speaks to them today.

For French artist Alizée Gazeau, Venice’s watery context was a natural invitation to create works using fishing nets and glass buoys, both a nod to the early ‘lagoon dwellers’ or fishermen who inhabited these marshy areas even before the city’s foundation and an acknowledgement of the role this profession continues to play in the diet and economy of Venetians to this day. In ‘Océanicité’ (Oceanicity), Gazeau is particularly interested in objects, such as nets, created by humans as a way of interacting with nature, or, in this case, capturing it. Working primarily on a grand scale (with some works measuring up to seven meters long) she unfurls large sail-like expanses of canvas on the floor before stretching nets saturated with water and deep purple-red pigments out across them. Gazeau then manipulates and layers the water, pigments and nets in instinctive and responsive ways to create an effect that she likens to the stormy seas famously described by the ancient Greek poet Homer in the ‘Odyssey’ as ‘wine-dark.’ In regularly (but not exclusively) working on this scale and in this way, Gazeau’s artistic process becomes a highly physical series of movements, almost a performance in itself. Her chosen media of canvas, nets and water evoke not only the seafaring Venetian way of life but also places her within the tradition of artists, such as those who adopted canvas as a support or the pioneers of arte povera, who innovate through restricting themselves to materials most readily available to them.

Having placed her nets and saturated her canvas or, in some cases, wood panel, Gazeau often then leaves the work in the studio to allow it to dry and take form. Once the paint has dried, she returns to peel back the net and reveal her finished painting, an imprint or negative record of the removed object. Gazeau’s interests however are not solely material but also metaphorical. Indeed, she describes the nets as both surfaces and portals in the way that they allow paint and water to pass through their matrices, yet are also retentive. Further, she likens these nets and their impressions to a kind of personal diary which preserves the memory of her research, its processes and the evolution of an idea.

La Red de Pesca: Espacio-Tiempo entre Mundos, La condición postnatural, Glosario de ecologías para otros mundos, Cthulhu Books, Madrid, 2024

Häutung, solo exhibition at Gr_und with the support of the French Institute, Berlin, 2023

AN END TO A SENTENCE

a conversation between Alizée Gazeau and Lisa Deml

HÄUTUNG, solo exhibition at Gr_und with the support of the French Institute, Berlin, 2023

Lisa Deml: The impression that settled on my mind when I first came to see this series of painting in your studio was that of maturity. To me, these paintings are a very clear and condensed expression of different lines of thought and experimentation that you have been following for several years. They seem to have grown through practice and now coincide with your first solo exhibition. How is this exhibition situated in your artistic development, what does it mean to mark this point in time?

Alizée Gazeau: I consider this exhibition as an opportunity to end a first sentence. I invoke the notion of a sentence, but you could also say it marks the end of a first journey. My work is concerned with process itself and I have the feeling that I could develop the same idea further indefinitely. In this sense, the exhibition at gr_und is also a challenge for me to put an end to this process. Even though I would never say that this process is finished, I have reached a point when I can let it settle down and let go. When the work enters into an exhibition space, it does not belong to me anymore, it is not about me anymore—the work has to speak for itself, as Louise Bourgeois would insist. She says that an artwork has nothing to do with the artist; it has to stand for itself. I find this credo helpful to navigate the tension between the intimacy inherent in artworks and the extrovert nature of exhibitions.

This is not only your first solo exhibition but also the first time that you work in painting and to this scale. How did you arrive at this discipline and format of 200 x 300 cm? Would you say that it is the result of a measure of trust and confidence you have gained in the process?

I felt the need to not only engage the hand and the eye in the work process but to involve the whole body. It is a very physical process as I work on the floor and pull and place the hammock and the net on the canvas. And it is not only a physical experience for me in the production process but also for the viewer in front of the paintings. I wanted the paintings to be bigger than us, so that they create an immersive sensation that exceeds the human body.

Given the expansive format of these paintings, how do you approach the canvas to begin with?

The paintings make me as much as I make them. It is a conversation between me and the various materials involved in the process, the canvas, the net, the hammock, colour and water. With these components, I create an environment, a framework within which the painting can emerge. Of course, the work process is different with every painting, there are different layers and rhythms at play each time. But what characterises my process is that I organise a situation on canvas and then leave the studio while the painting takes form. I return to it when everything has dried and I can remove the hammock and net to discover how they have impressed themselves on the surface. I very much enjoy this moment of revelation because it is often surprising. It is almost like a laboratory where I arrange the experimental setup and observe how it develops on its own. It is a delicate balance between controlling and letting go. While the first part of the work process is determined by my decisions and choices, the second part is beyond my command. So, even though this series of works are undeniably paintings, I would not call myself a painter.

What I find remarkable about your artistic practice is that all the components and materials that are involved in the production process retain a certain degree of agency and autonomy. This becomes most pronounced in the way in which you interact with the surface of the canvas. I know that you have given much thought to the notion of the surface—could you talk about what the surface is to you?

Of course, factually, paintings are two-dimensional, they have a flat surface. But I try to expand this understanding and to experiment with a sense of depth in my paintings. I want to create a sensation of the paintings coming towards you as you face them and dive into them. To me, this is also a reflection on what it takes to be an artist. At some point, I questioned myself and whether I am ready to be an artist or not. And an answer to this question is related to being ready to dive, to venture beyond the surface, and to confront memories and feelings of doubt and darkness. Producing these paintings was an almost physical experience of diving in and resurfacing to catch my breath. I think of these paintings as permeable surfaces. In a metaphorical way, they are questioning the idea of the skin, which is exposing you to the world at the same time as it is protecting you from it. To some extent, producing and showing paintings could be considered a healing process, not only for the artist but also for the people seeing them, as an instance of taking care.

As you mentioned the idea of the skin, this takes us to the title of the exhibition —Häutung. This notion of skinning seems to resonate on so many levels with your artistic practice, with the paintings themselves and their aesthetic impression, as well as with your work process and development as an artist. How do you relate the idea of Häutung to your practice?

As my work is concerned with the process itself, it is strongly connected to the concept of metamorphosis. For me, the process of printing relates to a continuous struggle to come to terms with the perpetual evolution and movement in which we are all implicated. Printing or imprinting are ancestral practices, ways to experience or own existence, for instance through handprints in stone or fossils. I had already produced prints with different found objects from the environment when I found the fishing net. It reminded me of fish skin itself—an interesting paradox, that the net mimics that which it is supposed to catch. The hammock is also a curious object that is allowing us to lie down and rest in nature, precisely by protecting us from the natural ground. Eventually, I moved away from natural elements towards tools that humans produced in order to enter into a conversation with what is called “nature”. In many ways, this is very similar to artistic practice, and to my artistic practice in particular. Both the hammock and the net are permeable and ambivalent between controlling or letting go. And once I have printed them on canvas, they become something else altogether and take on a second life.

The paintings offer a very immersive experience. Initially, I thought of them as cartographies but, rather than looking onto a landscape from above, they seem to draw one into the landscape, into a submerged perspective. Agnes Martin once said that, to her, painting was like going into the field of vision, as you would cross an empty beach to look at the ocean. I consider this to be a very fitting description of these paintings, an invitation to look beyond them.

This is one of my favourite quotes of Agnes Martin and it resonates strongly with me. Of course, the paintings have a physicality and presence but I hope that they, in a way, disappear behind themselves. Each painting holds a space that not only unfolds spatially but also temporally. Perhaps it is for this reason that I always work in series, to express a certain rhythm, a perpetual movement or evolution. While each painting is a work in and of itself, it is also part of a larger whole, of a score or sentence. In the exhibition at gr_und, I will continuously change the composition and chronology of the paintings so that the viewing experience will be different at every visit to the gallery. In this respect, my curatorial approach correlates with my artistic practice as they are both concerned with the process itself and with keeping this process alive. This might come out of a fear of completion and stasis, but I want to think of it as an openness towards fluidity. To me, fluidity is a good word to indicate a method of working rooted in humility, in acceptance of incompleteness, and a sense of reverence for the material at hand, for the unfolding process, for the shared space, and for the other artists and their work. Fluidity as a working method is especially important in collaborative projects, and the experience of curating the group show Off Water was exemplary in this respect. It felt very rewarding to work with all these artists, all women artists, I should say.

As I understand it, the notion of fluidity that you suggest is correlated with a tendency towards permeability. Would you agree?

Certainly. However, it is not only a poetic concept but born out of necessity, too. Over the last few years, as I have been developing my working method, I realised that it is impossible for me to control the entire production process. I had to allow myself, after setting the framework for production in the studio and performing my part, to give in to the process and leave the painting as it was taking form. This is where my sense of humility and reverence for the material and process comes from and, at the same time, where I arrived at a form of liberation or emancipation in my working method. I freed myself from any expectations I might have had towards the working method and developed a production process that most closely aligns with my perception of these paintings. For the first time, I feel that the way I am working corresponds with the ideas I am thinking through. And perhaps this is where the impression of maturity arises that you mentioned at the beginning.

In the exhibition at gr_und, you not only present this series of largescale paintings but also two sculptures and a textile work that you bring together in a material assemblage. In contrast to the paintings in whose expansiveness one can get lost, these sculptural pieces are very condensed and highly plastic.

In fact, the two sculptures are saddles that I found at a stable. Similar to the fishing net and the hammock, the saddle is a tool produced by humans in order to communicate with nature. The saddles were lying upside down on the floor of the stable and I was surprised to find that they looked like flowers or vulvas. Even though the common notion of horse riding and the dimension of power and control associated with it are rather masculine, when turned upside down I found the saddles to be very feminine objects. I was intrigued by how the quality and meaning of an object could be shifted simply by looking at it from a different perspective. The same shift happens when an object enters an art space where the saddles are now installed on a wall as art pieces. Strictly speaking, they are not sculptures because I did not produce them but they become sculptural through their exhibition. And I present them in an assemblage with a piece of fabric that I found on the street when I first moved to Berlin. I cut it in rhombus-shaped pieces echoing the pattern of the fishing net and the hammock and sowed it back together. The rhombus is a symbol for femininity in many cultures as well as the basic form of a mandorla which is used in Christian iconography to frame religious figures. As part of the exhibition, the fabric with its rhombic pattern might be associated with a cocoon or discarded skin. But it is very important for me that each piece in the exhibition is open to manifold interpretations and invokes different associations that are all valid.

I cannot help but think of Louise Bourgeois again, not only her insistence on the autonomy of the artwork in interpretation but also her process of doing, undoing, and redoing that you have just described. The fact that this work of doing, undoing, and redoing is never done, that there is never a moment of completion—does that not feel exhausting?

It is exhausting and yet essential that there is something that remains unresolved and that drives the process onward through continuous questions. To evoke Agnes Martin’s words again, she defines the artist as someone who wants to quit everyday but continues anyway. It is exhausting at the same time as it is healing. There are these moments when I return to the studio and remove the nets from the painting to see how it has taken form—and to find that something has happened that resembles an answer or an end to a sentence.

If a clod be washed away by the sea (after John Donne), 18, 2020

"No Man is an Island entire of Itself", Catalogue Art Theorema #3, Fondazione Imago Mundi Benetton, 2022

Art Connect Magazine, Interview with Lisa Deml, 2022

Le Filet, curated by Rio Usui, Ona Project Room, Tokyo, 2022

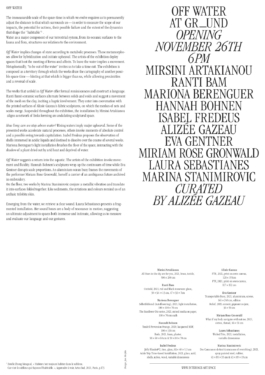

Off Water II, curated by Alizée Gazeau, Sainte Anne Gallery, Paris, 2022

Off Water I, curated by Alizée Gazeau, Gr_und, Berlin, 2021

Versa curated by Lisa Deml for Interface, Salon am Moritzplatz, Berlin, 2022

Harmony, issue 4, Presentation of Publication d'Art Non linéaire, Pierre Soulages Museum, Rodez, 2022

Interfaces, or those who caress the surface curated by Alizée Gazeau, Interface Berlin, 2021

Prize of les amis du National Museum for women in the arts, 2020

The physical exchanges rendered impossible by a lockdown imposed on almost all continents allowed the creation of unprecedented forms of communications. The first special edition titled Dièse, was elaborated during this period.

Seventy-five artists, choreographers, architects, publishers, singers, authors, critics, curators, and journalists were invited to contribute with a word, in the language of their choice.

The resulting artwork was silk-screen printed on cotton at Paris Print Club. It will be returned to the participants in the form of a collective score containing their imprint.

The words follow one another horizontally on category lines forming islands of meaning and correspondences.

Nothing's gonna change my world, Raumwww, Berlin, 2020

Recognition, issue 2, Publication d'Art Non linéaire, Voltaire Emerige, Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, 2019

But are we the only dreamed ones? curated by Faidra Vasileiadou, Daily Lazy Projects, Athens, 2019

The reason of the exhibition, "But are we the only dreamed ones?" is the exchange of correspondence between Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan, two of the most important figures of poetry and literature of the 20th century. Their dramatic and impassioned relationship was formed by the reciprocity of their letters, which for nearly 20 years relieved their existential quest while at the same time shaping their poetic works. A remarkable feature of this union is the creation of a peculiar linguistic grid, based on love and arguing, forming dense poetry with secret echoes.

Somewhere here lies the issue of this exhibition, the invention of a personal "language", romantic and yet erotic, to the artist himself, an alphabet that only empathy and trauma can pronounce. Observing the dipoles developing between the artist and the artistic formation, this relationship is undoubtedly a romance and is wrapped up with the invention of this personal idiom. Not infrequently, fragments of this language are scattered throughout their works. Small gestures, a different observation of their artwork, ultimately betray the character that this exhibition wants to enlight: the artistic act consists of erotic words.

The viewer is invited to discover the subcutaneous romanticism of the three young artists participating in the exhibition. Eleni Tsamadia, Alizée Gazeau and Konstantinos Giotis, through different prisms, confirm the existence of the lost language of the lovers. Love is not limited to the Other, as artists use romantic gestures to approach existence, contestation, the journey of the artist, the artistic creation itself. Harvesting the subconscious, observing the points that are not visible, are driven by the shadows collecting fragments - losses and dreams - where they eventually generate their own alphabet: a language of the dreamed ones.

"Life is not going to accommodate us, Ingeborg; waiting for that would surely be the most unfitting way for us to be. Be - yes, we can and are allowed to do so. To be - be there for another. Even if it is only a few words, alla breve, one letter once a month: the heart will know how to live."

Celan to Bachmann, 31 Oct. 1957

Joséphine Bindé for Beaux Arts Magazine, "Alizée Gazeau. Niché à Montmartre, un refuge pour les artistes", 2020

Joya:air arte e ecologia, Residency, Sierra Maria Los Velez, Spain, 2019

https://joya-air.org/artist/2019/4/22/joya-air-alize-gazeau-france

Horizons, issue 1, Publication d'Art Non linéaire, Paris, 2018

Residency at the Hartung Bergman Foundation, Antibes, France, 2018

Residency at the Artemis Studio, Ikaria, Greece, 2018

"HEUREUX QUI COMME ULYSSE"

Joséphine Dupuy Chavannat, "Heureux qui comme Ulysse", ("Happy who like Ulysses"), 2018

Une fenêtre ouverte sur la mer, un horizon au loin qui se dessine au moment où une ile émerge des flots. Ulysse. Dix ans d'errance pour atteindre sa partie. Dix ans de pleurs, d'espoir et d'aventures. Alizée Gazeau retrace le périple d'Ulysse, dont l'odyssée ne peut se lire sans l'omniprésence de la mer. Espace poétique, Ulysse la traverse pour se rendre vers un au-delà. Bouleversé, malmené, mais aussi transporté par les courants, l'état mental de l'Inventif se transpose au gré des états de l'eau. Oscillant entre les flots tourbillonnants, tels des champs de batailles, et le calme saisissant et serein des eaux marines, Ulysse est paradoxalement hanté et impatient par l'idée du retour. L'artiste interprète la polyphonie de la mer par l'intermédiaire de formes et de couleurs qui se répètent inlassablement d'un tableau à l'autre. On y retrouve ainsi l'île, le vaisseau, l'oubli, la patrie... comme on rencontre certains vers homériques d'un chant à l'autre, notamment le déchirant « Nous reprimes alors la mer avec tristesse » qui rythme sans relâche le récit. Alizée Gazeau capture ces éléments de l'épopée, les assemble et les éclate. Ils semblent alors suspendus sur la toile. Pourtant fixés à leur support, ils sont attirés par l'espace de la fenêtre qui s'ouvre sur une potentielle recomposition, un destin qui ne serait pas figé. Ensorcelé par son désir de retour, captivé par un horizon encore incertain, Ulysse tente, malgré les aléas des dieux, d'être maître du sort de la fin de sa vie. Composer les éléments avec maîtrise et liberté, voilà ce qui pourrait être le fil conducteur de cette série. Etape par étape, ile après ile, Ulysse reconquiert son royaume. Itape par étape, forme après forme, l'artiste révèle ce qui, pour elle, relève du processus créatif. Les draps tâchés de peinture et de térébenthine apposés sur la toile sont une manière pour l'artiste de sanctifier ce parcours initiatique. Elle ne se cache pas de ce qui relève de l'intime du peintre, comme le héros odysséen ne se cache pas de ses pleurs. Les formes associées aux éléments du récit, des larmes à l'oiseau, revêtissent progressivement une fonction musicale, si l'on entend l'Odyssée comme un chant homérique conté oralement, des aèdes antiques à Monteverdi. Les lignes d'horizon se transforment peu à peu en partition, alors que chaque élément pictural s'apparente aux notes d'une portée qui ne demande qu'à être activée par un ou plusieurs musiciens. Et s'il s'agit d'interpréter graphiquement le chant d'Homère, il est aussi profondément question, comme l'entend Gilles Deleuze, de «capter des forces», de poser un accord, chercher un équilibre pictural, musical, chromatique et poétique...

A window open onto the sea, a horizon in the far distance taking shape as an island emerges from the waves. Ulysses. Ten years of wandering to reach his land. Ten years of tears, hope and adventure. Alizée Gazeau retraces the journey of Ulysses, whose odyssey cannot be read without the omnipresence of the sea. A poetic space, Ulysses crosses it on a journey to the beyond. Shaken and battered, but also transported by the currents, the Inventive's mental state is transposed according to the states of the water. Oscillating between the swirling waves, like battlefields, and the striking, serene calm of the sea, Ulysses is paradoxically haunted and impatient by the idea of returning. The artist interprets the polyphony of the sea through forms and colors that are endlessly repeated from one painting to the next. We find the island, the ship, oblivion, the homeland... just as we encounter certain Homeric verses from one song to the next, notably the heart-rending "Nous retournons alors à la mer avec tristesse" (We return to the sea with sadness) that relentlessly punctuates the narrative. Alizée Gazeau captures these elements of the epic, assembles and explodes them. They seem suspended on the canvas. Yet fixed to their support, they are drawn into the space of the window, which opens onto a potential recomposition, a destiny that is not set in stone. Bewitched by his desire to return, captivated by a still uncertain horizon, Ulysses tries, despite the vagaries of the gods, to be the master of the destiny of the end of his life. Composing the elements with mastery and freedom could be the common thread running through this series. Step by step, island by island, Ulysses reclaims his kingdom. Step by step, form by form, the artist reveals what, for her, is the creative process. The sheets stained with paint and turpentine affixed to the canvas are the artist's way of sanctifying this initiatory journey. She does not hide from what is intimate to a painter, just as the Odyssean hero does not hide from his tears. The shapes associated with the story's elements, from the tears to the bird, gradually take on a musical function, if we understand the Odyssey as a Homeric song told orally, from the ancient aedes to Monteverdi. The horizon lines are gradually transformed into a musical partition, with each pictorial element resembling the notes of a stave, waiting to be activated by one or more musicians. And while it's a question of graphically interpreting Homer's song, it's also, as Gilles Deleuze puts it, a matter of "capturing forces", striking a chord, seeking a pictorial, musical, chromatic and poetic balance...

Alizée Gazeau (b. Paris, 1990) lives and works in Berlin. She holds a master's degree in art history from La Sorbonne, where she also studied philosophy of art.

Solo exhibitions include A Shadow’s Shadow, Sainte Anne Gallery, Paris, France (2025), I’m Herdsman of a Flock, Stallmann Galleries, Berlin, Germany (2024), Häutung, Gr_und with the support of the French Institute, Berlin, Germany (2023), Le Filet, Ona Project Room, Tokyo, Japan (2022), Heureux qui comme Ulysse, Bubenberg, Paris (2017).

Recent group exhibitions include Dream Weaving curated by Juliet Kothe and Azza Satti, Ambassade de France, Nairobi, Kenya (2025), Ballad of a runaway horse curated by Paulo Iverno, Paris, France (2025), éternelles errances, Centre Wallonie Bruxelles, Paris, France (2025), Jum Jum Jum, Pill, Seoul, Korea (2024), Mass, Spoiler Zone, Berlin, Germany (2024), H20 Venezia: Diari d’Acqua, Lapis Lazuli: artE with the support of the Fondazione Barovier&Toso, Venice, Italy (2024), Archive of Upcoming, Georg-Knorr Bremse Factory, Berlin, Germany (2023), Art Theorema Krisis, Fondazione Benetton, Trevise, Italy (2023), Off Water II, Sainte Anne Gallery, Paris, France, (2022), Interfaces, or those who caress the surface, Interface, Berlin, Germany (2021), But are we the only dreamed ones? curated by Faidra Vasileiadou, Daily Lazy Project, Athens, Greece (2019).

Alizée Gazeau was resident at the Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France (2019-2020, 2025), at La Chapelle Saint Antoine, Naxos, Greece (2024), at Lapis Lazuli: artE, Venice, Italy (2023), at the Fondation Hartung Bergman, Antibes, France (2018), at the Fondazione Michelangelo Pistoletto, Biella, Italy (2018), at Artemis Studio, Ikaria, Greece (2018) among others.

Between 2018-2022, she founded and edited Publication d'Art Non linéaire, a collective publication of artists and historians, giving rise to several events and conferences, at Musée Pierre Soulages, Rodez, France, at Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France, at Emerige Voltaire, Paris, France.

Fragment, 01,01, 2025, acrylic and ink on canvas, 120x90 cm

"A Knot is a Tight Place" written by Mariana Lemos and Mélanie Scheiner for Duets, edited by Mariana Lemos and Gigi Surel, London, June 2025

Studio, Nets used for painting, 2025, Berlin

Ballade of a Runaway Horse, a group show curated by Paulo Iverno, Paris, 2025

Sans titre P (worn-out saddle), 2025, horse saddle, approx. 60x80x40 cm & Sans titre (stirrups), 2025, leather, stirrups, variable dimensions

Théâtre National de Toulouse - CDN Occitanie

Dry River, 2025, acrylic on cotton canvas, 16m x 5,80m - a painting produced for the stage of Le Rêve d'Elektra by Clément Bondu, 2025

https://theatre-cite.com/programmation/2024-2025/spectacle/le-reve-d-elektra/

A Shadow's Shadow at Sainte Anne Gallery, March 7 - April 26 2025

A SHADOW'S SHADOW

a conversation between Alizée Gazeau and Joséphine Dupuy-Chavanat

Joséphine Dupuy-Chavanat: “ To title is to write a little!” said Alechinsky in 1911. Your first solo show was entitled Heureux qui comme Ulysse [Happy who like Ulysses], evoking the journey and the fragmentation of memory, while your second, Häutung [Molting], explored the idea of metamorphosis and the creative process. Recently, your much more conceptual exhibition I'm Herdsman of a Flock looked at the transformation, permeability and polysemy of familiar objects, particularly those from the marine and equestrian worlds. What motivated the title of this new exhibition at Sainte Anne Gallery?

Alizée Gazeau: A Shadow's Shadow is a quote from Hamlet. The exhibition is the first personal presentation of my paintings and sculptures in Paris after four years living in Berlin. I wanted to compose a series of paintings based on past and recent sensations, like the cast shadows of memory. Shadows come with light. The shadow of a shadow is two lights on objects that project onto each other. I like the idea of repetition, of the same word, the same motif, like a rhythm, a poem, a dance. A little further on, Shakespeare writes 'a dream itself is but a shadow'. In the paintings, we recognize the object of the net, the hammock, but as in a dream, it is no longer exactly the object, nor its abstraction. Three ensembles of sculptures punctuate the exhibition. They follow on from the horse saddle sculptures exhibited in November at Stallmann Galleries in Berlin.

So there's a fluidity, a kind of interstice that you constantly capture in your work. A moment that also seems suspended, between two states. The net, for example, seems to escape us the moment it appears. As for the leather straps, they play on the varying degrees of tension in their braiding, fused at one end and loose at the other. You mentioned recent sensations. Can you tell us what they are and how they may have influenced the paintings and sculptures presented here?

You said that the exhibition of horse saddle sculptures was more conceptual than previous ones. This is true and paradoxical at the same time, because it marks a moment when I have fully assumed the part of sensitive intuition in my work. The horse saddles, the braids made from their girths, the pieces cut from leather are sensual elaborations that respond to a very direct intuition. The net is an object I began collecting in 2019. Instability, loss and the fluctuating memory of a place are translated into painting through this object. Working on the ground, with pigments and water, it becomes a tool that allows me both to hold the paint on the surface of the canvas and to let it escape. There's a tension between letting go and holding back that I like to find in the process. As you say, we find the same tension between the idea of capture and liberation in the leather braids. These archetypal objects are like metaphors.

And what are these metaphors?

The idea of metaphor is that of a displacement from the original object. “Hammocks and fishing nets stem from ancestral practices. The oldest known fishing net in Europe dates from 8300 BC. The net in ancient Egyptian bas-reliefs functioned as a representational screen and can be seen as a metaphor for space and time.” In my paintings, the nets create spaces and capture events. The horse saddles are metaphors for the search for harmony between two beings, having an asymmetrical relationship. The sculpture Untitled (stirrups) is made of leather straps and stirrups. The stirrups, designed to maintain balance, are aligned vertically on the straps. They evoke a ladder, the axis mundi, that is, the connection between Heaven and Earth. When I speak of metaphor, I am referring to the idea that the work eludes definition, constantly projecting its form onto an infinite number of other thoughts.

I remember you sharing your thoughts with me when I was working on a project involving the graphic interpretation of music. You told me that between the appearance of a form and its disappearance, there exists a fragile compositional equilibrium. And painting - like music - seeks harmony. How does this quest for harmony, a subject that has long been dear to you, continue to infuse your work? I say “quest”, but perhaps you have found the right melody, the right rhythmic flow and the perfect consonance?

Yes, the word harmony was a recurrent theme. Music provokes instant emotions. I would like my paintings to be listened to and my sculptures to be perceived as a rhythm. This may sound abstract, but at the same time it is concrete in my works. Shapes appear as much as they vanish. I like them to produce a temporal, musical impression, something both anchored and fleeting. In the First Dance and Movement paintings, I searched for a perfect balance between light and darkness, a point of equilibrium between two opposites.

“The ocean is deathless - The island rise and die - Quietly come, quietly go - A silent swaying breath” Agnes Martin

I'm also thinking of Roni Horn, Sigmar Polke and Eva Hesse.

I do indeed remember the Sigmar Polke exhibition at Palazzo Grassi in Venice, which described the artist as “the painter of metaphors”. One of the huge works on show featured circus characters and animals balanced on chairs, buckets and ladders. Polke transforms and even metamorphoses his colors, like an alchemist. How do you work with materials and colors? Do you, like Polke, seek to create - through a singular use of pigments - a state akin to hypnosis?

I began imagining the paintings for the exhibition during a few weeks spent away from my studio. As always in my work process, I need to immerse myself in places, readings, conversations and emotions to prepare a new series. Back in the studio, a blending occurs between my intentions and the interactions that take place between pigments, paint, water, threads and the surface of the canvas. The paintings from the Surface series are made with a single color. I compose the painting by placing water-soaked nets on the canvas. By moving the pigments, the nets modify the pictorial surface, and after they are removed once dry the final painting appears. In this, I am also a kind of alchemist. There are certain colors that come up frequently: the contrast of black and white that structures the nets, the crimson color of bodily flows, of the sea in the Odyssey, of vital momentum. In the painting Suite, the fleeting shape of the net was almost enough on its own. I wanted to add a blue line to indicate temporality and movement. There is also the imprint of a net that traces a very low horizon line. You speak of a state close to hypnosis. What is certain is that I am led by my intuition, by the fluctuations of my memory and by the beauty of the absolute present offered by a painting in the making.

éternelles errances, curated by Marianna de Marzi, organized by Culturfoundry and les amis du NMWA, Centre Wallonie Bruxelles, Paris, 2025

Monopol, Interview Lina Stallmann with Hilda Dirks, 2025

"Davor, dahinter und immer weiter" by Beate Scheder for Die Tageszeitung, 17.12.2024

https://taz.de/Die-Kunst-der-Woche/!6054337/

I'm Herdsman of a Flock at Stallmann Galleries, November 24th - January 31st, 2025

Opening November 23rd 4-8pm

Jum, Jum, Jum, Orbit, curated by Rio Usui, at Plli, Seoul, photos Bokyoung Han

Residency at La Chapelle Saint Antoine, July 2024, Naxos, Greece

Bureau des arts plastiques, Institut Français de Berlin

Alix Weidner

From her studio in Berlin-Neukölln, Alizée Gazeau introduced us to her work on materiality. Based in Berlin for the past four years, the artist’s practice is mainly pictorial, but also includes installations. She is interested in intermediate surfaces that, like a fishing net or a glass float, lie between elements such as air and water. Other objects, such as a leather riding saddle or wooden tiles, stand between bodies and species, but also between bodies and spaces, and give food for thought about the contact surfaces that surround us and their permeability. For Alizée Gazeau, these objects are powerful points of interconnection, holding back or separating materials but also connecting entities. They give rise to rubbing and friction that, when fixed by paint on larges canvas or activated in installations, result in new symbiotic, organic and even dreamlike forms.

Alizée Gazeau’s pictorial work is at the same time restricted to a two-tone palette, while multiplying the effects of nuance and transparency on large imposing formats. She told us about her interest in the sea, which led her from the French Atlantic coast to the Venetian Lagoon, for water’s ability to penetrate substances and offer infinite interplays of tones and light. While her latest black-and-white pieces take up these forms of aqueous fluidity, they are also reminiscent of the photogram image. This photographic technique consists in placing objects on photosensitive paper to capture their direct form, giving both a formal or abstract rendering and, at the same time, a direct transcription of the objects used, i.e. an imprint of reality. This duality is reflected in the paintings of Alizée Gazeau, whose serial work cultivates and masters trouble from canvas to canvas.

MASS, group show at Spoiler Zone, Berlin, 2024

À propos des oeuvres d'Alizée Gazeau à Venise

Review by Christina-Marie Lümen, 2024

https://cmarthoughts.com/alizee-gazeau-lapis-lazuli-arte-venise/

H2O Venezia: Diari d'Acqua

text of the exhibition written by Laure Martin-Poulet, catalogue, Venice, 2024

H2O Venezia: Diari d'acqua

WATER AS A COMMON THREAD IN THE WORK OF ALIZÉE GAZEAU

text written by Laure Martin-Poulet

(...) Alizée Gazeau develops in this way a poetic and meditative body of work, leaving ample room for experimentation and for chance. She seeks to offer the viewer the freedom of an appropriation, a personal immersion, based on the following postulation: ‘When the work enters into an exhibition space, it does not belong to me anymore, it is not about me anymore – the work has to speak for itself’ (interview with the artist by Lisa Deml, Berlin, January 2023). With this, Alizée Gazeau echoes the credo of Louise Bourgeois, who belongs to her personal pantheon of artists alongside Agnes Martin: ‘A work of art has nothing to do with the artist, a work of art has to stand by itself’ (Louise Bourgeois, ‘Destruction of the Father. Reconstruction of the Father’, 1998, p.168).

From the start, she approaches the question of landscape in painting and drawing through the bias of abstraction and metaphor. In 2016, in her very first series of works, aptly entitled ‘Incipit’, Alizée Gazeau adopted the technique of collage, which she appreciates for the freedom it entails. Using as backgrounds old, very classic seascapes dating back to her classes at Ivry, upon which she arranged shapes cut from silk paper, she composes a fragmented landscape, seemingly shattered. Exploring the question of horizon, of the island as an imaginary utopian place, she created, during a trip to Cuba in 2016, a series of collages titled ‘Lines and Forms on Cuban Walls’. Upon her return, the reading of Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, inspired a new series of collages presented in her first solo exhibition, in October 2017 at Bubenberg Gallery in Paris, with the title ‘Heureux qui comme Ulysse’ (Happy who like Ulysses). From Homer’s story, she extracted words that she transposed into coloured figures on fabric, affixed to the canvas, forming an archipelago of sorts. Earlier that same year, during a stay at La Baule, Alizée Gazeau created ‘Silence and Noise’, a work composed of a glass plate with collages of abstract silk paper shapes, yet again evoking the idea of islands, and a frame on which hangs white silk gauze. She made it the subject of an ins- tallation-performance, of which she has preserved the memory in a series of black and white photographs. On the beach, Alizée Gazeau moved the glass plate, and the shadows of the collages were cast onto the silk sail attached to the frame planted in the sand. This was an important moment, which she remembers: ‘For the first time, I felt I could trust my intuition, and escape the convention of painting, the collage’*. This initiatory experience continues in other works, by summoning the action of natural elements, she incorporates the random, the unexpected.

This way, in February 2020 in La Baule, Alizée Gazeau, while seeking out an idea for an invitation card, made a cyanotype of a fishing net, which she printed on canvas, before affixing it to a salvaged wooden pallet and placing it at the water’s edge to photograph it. The waves suddenly swept away the work, transforming it into a raft adrift, like the aftermath of a shipwreck. On the spot, she transformed this incident into an improvised performance, capturing it in a series of photographs titled ‘If a clod be washed away by the sea (after John Donne)’. In an unsettling coincidence, just a few weeks later, the Covid pandemic upended the entire world.

But let us return to spring 2018, when a significant turning point occurred on the occasion of a first artist residency on the island of Ikaria in the Aegean Sea: the transition from collage to imprint. Embracing this ancestral technique, the artist made there her very first imprints with cotton fabrics soaked in pigments collected on site and mixed with acrylic and water from the river Halaris, which gives the series its name. She continued in this new direction with other works made by using olive branches, with the title ‘OE_18’. These were made during her residency at the Hartung Bergman Foundation in Antibes in September 2018, where Alizée Gazeau found material for her art in the surrounding nature, a source of inspiration for the work of Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman, with invaluable encouragement and support from Thomas Schlesser.

Continually striving to go beyond the ‘surface of things’* in a fluid gesture involving not only the eye and hand, but the entire body, Alizée Gazeau explores new practices and materials, while remaining in the register of abstraction, which grows in corporality without losing its lyricism.