YEAR

OBJECT

MATERIAL/DIMENSIONS

INFOS

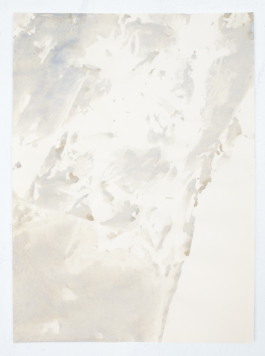

2025

hammock

acyles and ink on canvas - 260x240 cm

Composition_02,11

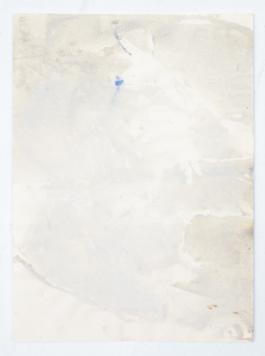

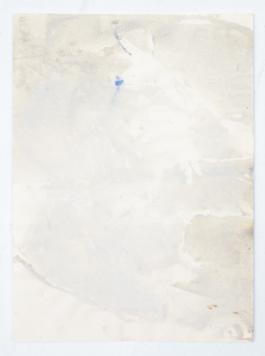

2025

glass float nets

rope

untitled

2025

glass float net

acrylique and ink on canvas - 160x140 cm

Interval_02,11_25

2025

hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 190x120 cm

Suite_series

2025

hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 190x120 cm

Suite_06,10

2025

stirrups

leather - variable dimensions

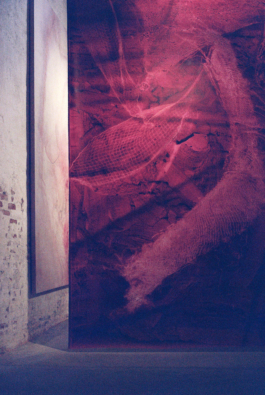

Untitled (stirrups) - A Shadow's Shadows - solo show at Sainte Anne Gallery, 2025

2025

hammock

acrylic on canvas - 190x120 cm

Surface

2025

hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 190x120 cm

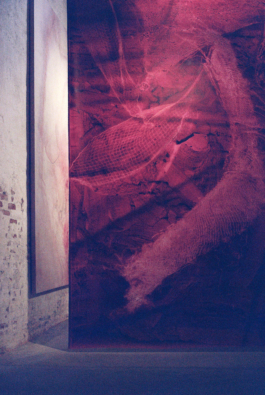

paintings - A shadow's Shadow, Sainte Anne Gallery - Paris

a conversation between Alizée Gazeau and Joséphine Dupuy-Chavanat

Joséphine Dupuy-Chavanat: “ To title is to write a little!” said Alechinsky in 1911. Your first solo show was entitled Heureux qui comme Ulysse [Happy who like Ulysses], evoking the journey and the fragmentation of memory, while your second, Häutung [Molting], explored the idea of metamorphosis and the creative process. Recently, your much more conceptual exhibition I'm Herdsman of a Flock looked at the transformation, permeability and polysemy of familiar objects, particularly those from the marine and equestrian worlds. What motivated the title of this new exhibition at Sainte Anne Gallery?

Alizée Gazeau: A Shadow's Shadow is a quote from Hamlet. The exhibition is the first personal presentation of my paintings and sculptures in Paris after four years living in Berlin. I wanted to compose a series of paintings based on past and recent sensations, like the cast shadows of memory. Shadows come with light. The shadow of a shadow is two lights on objects that project onto each other. I like the idea of repetition, of the same word, the same motif, like a rhythm, a poem, a dance. A little further on, Shakespeare writes 'a dream itself is but a shadow'. In the paintings, we recognize the object of the net, the hammock, but as in a dream, it is no longer exactly the object, nor its abstraction. Three ensembles of sculptures punctuate the exhibition. They follow on from the horse saddle sculptures exhibited in November at Stallmann Galleries in Berlin.

So there's a fluidity, a kind of interstice that you constantly capture in your work. A moment that also seems suspended, between two states. The net, for example, seems to escape us the moment it appears. As for the leather straps, they play on the varying degrees of tension in their braiding, fused at one end and loose at the other. You mentioned recent sensations. Can you tell us what they are and how they may have influenced the paintings and sculptures presented here?

You said that the exhibition of horse saddle sculptures was more conceptual than previous ones. This is true and paradoxical at the same time, because it marks a moment when I have fully assumed the part of sensitive intuition in my work. The horse saddles, the braids made from their girths, the pieces cut from leather are sensual elaborations that respond to a very direct intuition. The net is an object I began collecting in 2019. Instability, loss and the fluctuating memory of a place are translated into painting through this object. Working on the ground, with pigments and water, it becomes a tool that allows me both to hold the paint on the surface of the canvas and to let it escape. There's a tension between letting go and holding back that I like to find in the process. As you say, we find the same tension between the idea of capture and liberation in the leather braids. These archetypal objects are like metaphors.

And what are these metaphors?

The idea of metaphor is that of a displacement from the original object. “Hammocks and fishing nets stem from ancestral practices. The oldest known fishing net in Europe dates from 8300 BC. The net in ancient Egyptian bas-reliefs functioned as a representational screen and can be seen as a metaphor for space and time.” In my paintings, the nets create spaces and capture events. The horse saddles are metaphors for the search for harmony between two beings, having an asymmetrical relationship. The sculpture Untitled (stirrups) is made of leather straps and stirrups. The stirrups, designed to maintain balance, are aligned vertically on the straps. They evoke a ladder, the axis mundi, that is, the connection between Heaven and Earth. When I speak of metaphor, I am referring to the idea that the work eludes definition, constantly projecting its form onto an infinite number of other thoughts.

I remember you sharing your thoughts with me when I was working on a project involving the graphic interpretation of music. You told me that between the appearance of a form and its disappearance, there exists a fragile compositional equilibrium. And painting - like music - seeks harmony. How does this quest for harmony, a subject that has long been dear to you, continue to infuse your work? I say “quest”, but perhaps you have found the right melody, the right rhythmic flow and the perfect consonance?

Yes, the word harmony was a recurrent theme. Music provokes instant emotions. I would like my paintings to be listened to and my sculptures to be perceived as a rhythm. This may sound abstract, but at the same time it is concrete in my works. Shapes appear as much as they vanish. I like them to produce a temporal, musical impression, something both anchored and fleeting. In the First Dance and Movement paintings, I searched for a perfect balance between light and darkness, a point of equilibrium between two opposites.

“The ocean is deathless - The island rise and die - Quietly come, quietly go - A silent swaying breath” Agnes Martin

I'm also thinking of Roni Horn, Sigmar Polke and Eva Hesse.

I do indeed remember the Sigmar Polke exhibition at Palazzo Grassi in Venice, which described the artist as “the painter of metaphors”. One of the huge works on show featured circus characters and animals balanced on chairs, buckets and ladders. Polke transforms and even metamorphoses his colors, like an alchemist. How do you work with materials and colors? Do you, like Polke, seek to create - through a singular use of pigments - a state akin to hypnosis?

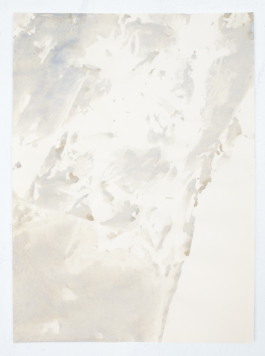

I began imagining the paintings for the exhibition during a few weeks spent away from my studio. As always in my work process, I need to immerse myself in places, readings, conversations and emotions to prepare a new series. Back in the studio, a blending occurs between my intentions and the interactions that take place between pigments, paint, water, threads and the surface of the canvas. The paintings from the Surface series are made with a single color. I compose the painting by placing water-soaked nets on the canvas. By moving the pigments, the nets modify the pictorial surface, and after they are removed once dry the final painting appears. In this, I am also a kind of alchemist. There are certain colors that come up frequently: the contrast of black and white that structures the nets, the crimson color of bodily flows, of the sea in the Odyssey, of vital momentum. In the painting Suite, the fleeting shape of the net was almost enough on its own. I wanted to add a blue line to indicate temporality and movement. There is also the imprint of a net that traces a very low horizon line. You speak of a state close to hypnosis. What is certain is that I am led by my intuition, by the fluctuations of my memory and by the beauty of the absolute present offered by a painting in the making.

2025

riding stirrups

leather - variable dimensions

untitled (braid)

2024

fishing net - hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 120x90 cm

Low Tide

2024

worn out saddle

horse saddle - variable dimensions

Untitled (worn-out saddles) - I'm Herdsman of a Flock - solo show at Stallmann Galleries - Berlin

https://www.contemporaryartlibrary.org/project/alizee-gazeau-56518

2024

hammock

acrylic and ink in canvas - 190x120 cm

Négatif_1, Suite 2_3, Stallmann Galleries - Berlin

2024

worn out horse saddles

two saddles - variable dimensions

Stallmann Galleries - I’m Herdsman of a Flock - Berlin

Text by Christina-Marie Lümen

Alizée Gazeau presents I’m Herdsman of a Flock at Stallmann, Berlin, an installation of 17 horse saddles mounted in a straight line on a gray wall. The installation is minimalistic, an impression emphasised by the gray colour of the wall alluding to concrete. The strict mounting, sleek leather, and sharp forms create a radicality forcing its presence onto us.

The saddles are presented upside down, with their insides facing the viewer, the flaps outstretched. The variety of positions among the same object recalls sheep of a herd; some are resting, some are fighting, some shy, others showing up.

Gazeau first started working with the saddles in 2020 after finding one at her friend Raoul’s stables in Yvelines. What struck her was the changed nature of the saddle when being turned around; suddenly, it became a flower, a butterfly, a womb.

Transformation is at the core of Gazeau’s artistic practice. In her paintings and sculptures, the artist takes objects of use out of their original position and function, employs them as artistic tool or turns them into puzzling encounters. The imprints of fishing nets become reptile skin and parchment; saddles become sheep, beetles and breasts.

Accordingly, the artist does not aim at representing an object. She wants to reduce the distance to reality, render an object perceivable by taking it out of its ordinary position and use, and opening up the manifold natures of what we think we know. This ability to change perspective, embrace the mysterious, and to subtly but deliberately include a – female – sensuality into her work aligns Gazeau with artists such as Meret Oppenheim or Louise Bourgeois. The process is an evolution from Surrealism, the Objet trouvé and the readymade over Minimalism to a 21st century form. A metamorphosis, giving the factual – concrete, object of use – a poetic touch.

Having completed a double degree in art history and philosophy before dedicating herself to her visual artistic practice, Gazeau finds inspiration in literature and poetry. The title of the exhibition is taken from The Herdsman (1925) by Fernando Pessoa (1988-1935), whose writings deeply influence Gazeau’s work.

I'm herdsman of a flock.

The sheep are my thoughts

And my thoughts are all sensations. I think with my eyes and my ears And my hands and feet

And nostrils and mouth.

To think a flower is to see and smell it. To eat a fruit is to sense its savor.

The poem expresses a shared artistic, and indeed life approach. Commenting on why Gazeau feels such a strong connection to the writer’s work, the artist names Pessoa’s ambiguity between being a grounded realist and utopian dreamer. By reducing the physical to its poetic and sensual existence, Gazeau confronts the essence of things; and she wants us to do so, too.

For Gazeau, I’m Herdsman of a Flock constitutes an artistic statement illustrating in a direct way Gazeau’s perception as an artist: She works with found objects in an intuitive and sensitive way.

In the gallery, the saddles amount to a flock. Stallmann is becoming a stable for the lost sheep of sensation.

2024

greek table cloth

acrylic on jute canvas - 140x100 cm

Eleonas_1

2024

hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 190x120 cm

Surface series

2024

fishing nets

acrylic and ink on canvas

Installation Lapis Lazuli:arte

Letters with Liberty Adrien, Catalogue Venezia: Diari d'Acqua

Berlin, Tuesday 16 January 2024

Dear Liberty,

I wanted to tell you about my outing on the Lagoon on 2 October 2023. I met Pietro Consolandi at Piazza Santa Maria Elisabetta on the Lido to take a boat ride. The horizon widened. The Lagoon stretched from barena to barena, and I felt like I was in the heart of an organic archipelago, in the lungs of this whole body that was seeking to reach the ocean. The samphire was red, mingling with heather, and we went along Sant’Erasmo at low tide. I was there, plunged into this thickness of duration that Henri Bergson defines as composed of two parts: our immediate past, and our imminent future. Conscious, therefore, of a memory I had come there to preserve.

Venice, 7 December 2023. In the studio, a series of paintings float, hanging from the mezzanine, made over these past three months in Venice. The paintings are supple, flowing; they flutter as soon as I open the door to go out to the garden. They remind me of a sentence Lisa Robertson wrote in The Baudelaire Fractal, ‘Time in water is pliable’. Time in Venice has unfolded gradually over these past few months, like the current of a stream gradually turning into a torrent. I’m facing the paintings. They are red, purple, pink, wrung from the mesh of the nets I used to paint them. Red is the colour of the pulse of life, and purple, that of the Mediterranean in Homer’s Odyssey, frequently threatening and thus, vinous. The paintings evoke an imminent immersion: they stand like flags, freely, sails enveloping their surfaces like a second skin. The other day, you asked me what part of my work is autobiographical. When I came to Venice, I had the term oceanicity in mind, the degree to which the climate is affected by the influence of the sea. I come from the Atlantic coast, from the French departments of Finistère and Loire-Atlantique. My maternal great-grandfather Ester was an Italian immigrant who worked as a mason. He settled in Brest and married Jeanne, who would become a fabric merchant. My grandmother worked for years with her mother in her fabric shop, Le Dès d’Argent in Brest. We always exchanged a lot about colours, textures, fabric and how to preserve, reinvent, fabricate. Her entire memory has been enshrouded in a thick fog, but just recently, we talked more about colours and did some sewing together. The idea of oceanicity allowed me to question myself about the capacity of streams of memory to spark my creativity and the stories of others, my empathy, like an ocean current. Memory is the imprint of reality on the surface of thought. The imprint, as Georges Didi-Hubermann writes, ‘is firstly a gap that is printed, touching and even ‘impressing’ us, in its distinctive and inaccessible memory of contact’. I think my paintings propose a form of living with change, with the fluctuations of thought. What do you think of the idea of inner landscape?

I’d like to end this letter with another sentence by Lisa Robertson: ‘The distinction between inner and outer worlds was becoming permeable and supple, like a fabric, which is in its very technical constitution both structure and surface’.

Warm regards,

Alizée

Frankfurt, 28 January 2024

Dear Alizée,

‘When they went ashore the animals that took up a land life carried this them a part of the sea in their bodies, a heritage with them passed on to their children and which even today links each land animal with its origin in the ancient sea. Fish, amphibian, and reptile, warm-blooded bird, and mammal – each of us carries in our veins a salty steam in which the elements sodium, potassium and calcium are combined in almost the same proportions as in sea water.’ Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us

In recent days, I have plunged back into Rachel Carson’s book, The Sea Around Us. The first work in a trilogy published in 1951, her words weave together poetry and scientific knowledge in an extraordinary exploration of the ocean’s depths and its history. The writer’s representation of the language of the sea made me think of you, in how your series of paintings could be a fragmentary transposition of this.

The notions of layers, sediments, lights and colours, at the heart of your artistic process and essential components of oceanography, have particular resonance. In her book, Carson explores the ‘vertical migration of the layer’ between surface waters, deep waters and undersea reliefs, ensuring undersea life through ‘a series of delicately adjusted, interlocking relationships’. The verticality and essence of these interactions reflect the ones inherent to your works. The paper spread out on the ground, the fishing net placed upon it, the liquid saturated with colour and minerals enveloping them, and the chemical and physical reactions arising from their interactions – of earth (gravity), air (evaporation) and light (colour change) –form your paintings. Once the water has evaporated, leaving behind its deposits in the nooks of the net, which has been carefully removed, a map of traces and processes remains, a representation of reliefs and histories. ‘The sediments are a sort of epic poem of the earth’, Carson writes. Their nature and their arrangement recount the history of the seas and oceans – they are the imprint of relationships.

In your letter, you touch on associations and attributions of colours, relating to your body of work, your biography and your perception of landscapes. These complex interactions between visual and sensorial impressions influence our ever-changing reception of the colours of the seas and oceans. Our vision is affected by the presence of living bodies, microorganisms, molecules and reliefs, as well as by sunlight, heat, time of day and season. Our senses are stimulated by the emergence of memories, places and moments experienced or known, prompted by this contemplation.

The evocation of your personal and familial ties to Finistère, and your interest for the notion of inner landscape, brought to my mind the North Sea coast, in northern France, where I spent much of my childhood. Its landscape has been shaped by two powerful forces: that of strong tides and ruins from History. Every day, the sea, subjected to the pull of the moon and sun, withdraws, sometimes kilometres, revealing a perpetually changing topography of sand. Its windswept dunes, standing opposite the ‘vast world of sea and sky’, as Carson writes, are marked by the spectral, imposing presence of blockhouses. These concrete buildings, attesting to the German army’s occupation during World War II, hold an immense sense of desolation and violence. They’re slowly sinking into the sandy ground, as though the earth were swallowing them up. The striking forces of the natural world here seem to confront Humanity’s fragility. This was my first reception of deep emotions emanating from a landscape. I’ve gone over wordcount, and the hour is late, so I’ll end my letter with a request: I’m curious to know more about your relationship with the notion of Oceanicity.

Looking forward to hearing back from you soon.

Warmest,

Liberty

2024

glass float

glass float - fabric

untitled (glass float)_2

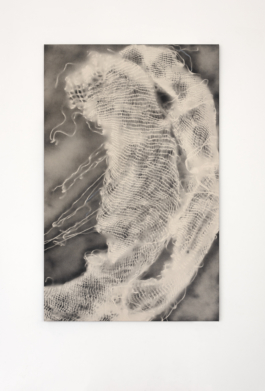

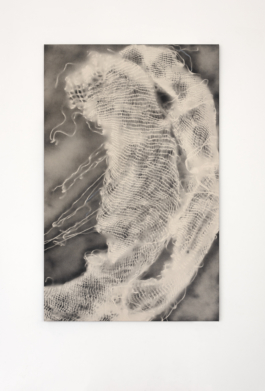

2023

fishing nets

acrylic and ink on canvas - 300x190 cm

Haütung - Gr_und - with the support of the French Institute - Berlin

AN END TO A SENTENCE - a conversation between Alizée Gazeau and Lisa Deml

Lisa Deml: The impression that settled on my mind when I first came to see this series of painting in your studio was that of maturity. To me, these paintings are a very clear and condensed expression of different lines of thought and experimentation that you have been following for several years. They seem to have grown through practice and now coincide with your first solo exhibition. How is this exhibition situated in your artistic development, what does it mean to mark this point in time?

Alizée Gazeau: I consider this exhibition as an opportunity to end a first sentence. I invoke the notion of a sentence, but you could also say it marks the end of a first journey. My work is concerned with process itself and I have the feeling that I could develop the same idea further indefinitely. In this sense, the exhibition at gr_und is also a challenge for me to put an end to this process. Even though I would never say that this process is finished, I have reached a point when I can let it settle down and let go. When the work enters into an exhibition space, it does not belong to me anymore, it is not about me anymore—the work has to speak for itself, as Louise Bourgeois would insist. She says that an artwork has nothing to do with the artist; it has to stand for itself. I find this credo helpful to navigate the tension between the intimacy inherent in artworks and the extrovert nature of exhibitions.

This is not only your first solo exhibition but also the first time that you work in painting and to this scale. How did you arrive at this discipline and format of 200 x 300 cm? Would you say that it is the result of a measure of trust and confidence you have gained in the process?

I felt the need to not only engage the hand and the eye in the work process but to involve the whole body. It is a very physical process as I work on the floor and pull and place the hammock and the net on the canvas. And it is not only a physical experience for me in the production process but also for the viewer in front of the paintings. I wanted the paintings to be bigger than us, so that they create an immersive sensation that exceeds the human body.

Given the expansive format of these paintings, how do you approach the canvas to begin with?

The paintings make me as much as I make them. It is a conversation between me and the various materials involved in the process, the canvas, the net, the hammock, colour and water. With these components, I create an environment, a framework within which the painting can emerge. Of course, the work process is different with every painting, there are different layers and rhythms at play each time. But what characterises my process is that I organise a situation on canvas and then leave the studio while the painting takes form. I return to it when everything has dried and I can remove the hammock and net to discover how they have impressed themselves on the surface. I very much enjoy this moment of revelation because it is often surprising. It is almost like a laboratory where I arrange the experimental setup and observe how it develops on its own. It is a delicate balance between controlling and letting go. While the first part of the work process is determined by my decisions and choices, the second part is beyond my command. So, even though this series of works are undeniably paintings, I would not call myself a painter.

What I find remarkable about your artistic practice is that all the components and materials that are involved in the production process retain a certain degree of agency and autonomy. This becomes most pronounced in the way in which you interact with the surface of the canvas. I know that you have given much thought to the notion of the surface—could you talk about what the surface is to you?

Of course, factually, paintings are two-dimensional, they have a flat surface. But I try to expand this understanding and to experiment with a sense of depth in my paintings. I want to create a sensation of the paintings coming towards you as you face them and dive into them. To me, this is also a reflection on what it takes to be an artist. At some point, I questioned myself and whether I am ready to be an artist or not. And an answer to this question is related to being ready to dive, to venture beyond the surface, and to confront memories and feelings of doubt and darkness. Producing these paintings was an almost physical experience of diving in and resurfacing to catch my breath. I think of these paintings as permeable surfaces. In a metaphorical way, they are questioning the idea of the skin, which is exposing you to the world at the same time as it is protecting you from it. To some extent, producing and showing paintings could be considered a healing process, not only for the artist but also for the people seeing them, as an instance of taking care.

As you mentioned the idea of the skin, this takes us to the title of the exhibition —Häutung. This notion of skinning seems to resonate on so many levels with your artistic practice, with the paintings themselves and their aesthetic impression, as well as with your work process and development as an artist. How do you relate the idea of Häutung to your practice?

As my work is concerned with the process itself, it is strongly connected to the concept of metamorphosis. For me, the process of printing relates to a continuous struggle to come to terms with the perpetual evolution and movement in which we are all implicated. Printing or imprinting are ancestral practices, ways to experience or own existence, for instance through handprints in stone or fossils. I had already produced prints with different found objects from the environment when I found the fishing net. It reminded me of fish skin itself—an interesting paradox, that the net mimics that which it is supposed to catch. The hammock is also a curious object that is allowing us to lie down and rest in nature, precisely by protecting us from the natural ground. Eventually, I moved away from natural elements towards tools that humans produced in order to enter into a conversation with what is called “nature”. In many ways, this is very similar to artistic practice, and to my artistic practice in particular. Both the hammock and the net are permeable and ambivalent between controlling or letting go. And once I have printed them on canvas, they become something else altogether and take on a second life.

The paintings offer a very immersive experience. Initially, I thought of them as cartographies but, rather than looking onto a landscape from above, they seem to draw one into the landscape, into a submerged perspective. Agnes Martin once said that, to her, painting was like going into the field of vision, as you would cross an empty beach to look at the ocean. I consider this to be a very fitting description of these paintings, an invitation to look beyond them.

This is one of my favourite quotes of Agnes Martin and it resonates strongly with me. Of course, the paintings have a physicality and presence but I hope that they, in a way, disappear behind themselves. Each painting holds a space that not only unfolds spatially but also temporally. Perhaps it is for this reason that I always work in series, to express a certain rhythm, a perpetual movement or evolution. While each painting is a work in and of itself, it is also part of a larger whole, of a score or sentence. In the exhibition at gr_und, I will continuously change the composition and chronology of the paintings so that the viewing experience will be different at every visit to the gallery. In this respect, my curatorial approach correlates with my artistic practice as they are both concerned with the process itself and with keeping this process alive. This might come out of a fear of completion and stasis, but I want to think of it as an openness towards fluidity. To me, fluidity is a good word to indicate a method of working rooted in humility, in acceptance of incompleteness, and a sense of reverence for the material at hand, for the unfolding process, for the shared space, and for the other artists and their work. Fluidity as a working method is especially important in collaborative projects, and the experience of curating the group show Off Water was exemplary in this respect. It felt very rewarding to work with all these artists, all women artists, I should say.

As I understand it, the notion of fluidity that you suggest is correlated with a tendency towards permeability. Would you agree?

Certainly. However, it is not only a poetic concept but born out of necessity, too. Over the last few years, as I have been developing my working method, I realised that it is impossible for me to control the entire production process. I had to allow myself, after setting the framework for production in the studio and performing my part, to give in to the process and leave the painting as it was taking form. This is where my sense of humility and reverence for the material and process comes from and, at the same time, where I arrived at a form of liberation or emancipation in my working method. I freed myself from any expectations I might have had towards the working method and developed a production process that most closely aligns with my perception of these paintings. For the first time, I feel that the way I am working corresponds with the ideas I am thinking through. And perhaps this is where the impression of maturity arises that you mentioned at the beginning.

In the exhibition at gr_und, you not only present this series of largescale paintings but also two sculptures and a textile work that you bring together in a material assemblage. In contrast to the paintings in whose expansiveness one can get lost, these sculptural pieces are very condensed and highly plastic.

In fact, the two sculptures are saddles that I found at a stable. Similar to the fishing net and the hammock, the saddle is a tool produced by humans in order to communicate with nature. The saddles were lying upside down on the floor of the stable and I was surprised to find that they looked like flowers or vulvas. Even though the common notion of horse riding and the dimension of power and control associated with it are rather masculine, when turned upside down I found the saddles to be very feminine objects. I was intrigued by how the quality and meaning of an object could be shifted simply by looking at it from a different perspective. The same shift happens when an object enters an art space where the saddles are now installed on a wall as art pieces. Strictly speaking, they are not sculptures because I did not produce them but they become sculptural through their exhibition. And I present them in an assemblage with a piece of fabric that I found on the street when I first moved to Berlin. I cut it in rhombus-shaped pieces echoing the pattern of the fishing net and the hammock and sowed it back together. The rhombus is a symbol for femininity in many cultures as well as the basic form of a mandorla which is used in Christian iconography to frame religious figures. As part of the exhibition, the fabric with its rhombic pattern might be associated with a cocoon or discarded skin. But it is very important for me that each piece in the exhibition is open to manifold interpretations and invokes different associations that are all valid.

I cannot help but think of Louise Bourgeois again, not only her insistence on the autonomy of the artwork in interpretation but also her process of doing, undoing, and redoing that you have just described. The fact that this work of doing, undoing, and redoing is never done, that there is never a moment of completion—does that not feel exhausting?

It is exhausting and yet essential that there is something that remains unresolved and that drives the process onward through continuous questions. To evoke Agnes Martin’s words again, she defines the artist as someone who wants to quit everyday but continues anyway. It is exhausting at the same time as it is healing. There are these moments when I return to the studio and remove the nets from the painting to see how it has taken form—and to find that something has happened that resembles an answer or an end to a sentence.

2022

fishing net

acrylic on canvas - 300x190 cm

H_22_1 & H_22_2

2018

olive tree branches

Drawings on paper - 20x30 cm

Olea Europaea - during a residency at the Hartung Bergman Foundation, France

YEAR

OBJECT

MATERIAL/DIMENSIONS

INFOS

2025

hammock

acyles and ink on canvas - 260x240 cm

Composition_02,11

2025

glass float nets

rope

untitled

2025

glass float net

acrylique and ink on canvas - 160x140 cm

Interval_02,11_25

2025

hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 190x120 cm

Suite_series

2025

hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 190x120 cm

Suite_06,10

2025

stirrups

leather - variable dimensions

Untitled (stirrups) - A Shadow's Shadows - solo show at Sainte Anne Gallery, 2025

2025

hammock

acrylic on canvas - 190x120 cm

Surface

2025

hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 190x120 cm

paintings - A shadow's Shadow, Sainte Anne Gallery - Paris

a conversation between Alizée Gazeau and Joséphine Dupuy-Chavanat

Joséphine Dupuy-Chavanat: “ To title is to write a little!” said Alechinsky in 1911. Your first solo show was entitled Heureux qui comme Ulysse [Happy who like Ulysses], evoking the journey and the fragmentation of memory, while your second, Häutung [Molting], explored the idea of metamorphosis and the creative process. Recently, your much more conceptual exhibition I'm Herdsman of a Flock looked at the transformation, permeability and polysemy of familiar objects, particularly those from the marine and equestrian worlds. What motivated the title of this new exhibition at Sainte Anne Gallery?

Alizée Gazeau: A Shadow's Shadow is a quote from Hamlet. The exhibition is the first personal presentation of my paintings and sculptures in Paris after four years living in Berlin. I wanted to compose a series of paintings based on past and recent sensations, like the cast shadows of memory. Shadows come with light. The shadow of a shadow is two lights on objects that project onto each other. I like the idea of repetition, of the same word, the same motif, like a rhythm, a poem, a dance. A little further on, Shakespeare writes 'a dream itself is but a shadow'. In the paintings, we recognize the object of the net, the hammock, but as in a dream, it is no longer exactly the object, nor its abstraction. Three ensembles of sculptures punctuate the exhibition. They follow on from the horse saddle sculptures exhibited in November at Stallmann Galleries in Berlin.

So there's a fluidity, a kind of interstice that you constantly capture in your work. A moment that also seems suspended, between two states. The net, for example, seems to escape us the moment it appears. As for the leather straps, they play on the varying degrees of tension in their braiding, fused at one end and loose at the other. You mentioned recent sensations. Can you tell us what they are and how they may have influenced the paintings and sculptures presented here?

You said that the exhibition of horse saddle sculptures was more conceptual than previous ones. This is true and paradoxical at the same time, because it marks a moment when I have fully assumed the part of sensitive intuition in my work. The horse saddles, the braids made from their girths, the pieces cut from leather are sensual elaborations that respond to a very direct intuition. The net is an object I began collecting in 2019. Instability, loss and the fluctuating memory of a place are translated into painting through this object. Working on the ground, with pigments and water, it becomes a tool that allows me both to hold the paint on the surface of the canvas and to let it escape. There's a tension between letting go and holding back that I like to find in the process. As you say, we find the same tension between the idea of capture and liberation in the leather braids. These archetypal objects are like metaphors.

And what are these metaphors?

The idea of metaphor is that of a displacement from the original object. “Hammocks and fishing nets stem from ancestral practices. The oldest known fishing net in Europe dates from 8300 BC. The net in ancient Egyptian bas-reliefs functioned as a representational screen and can be seen as a metaphor for space and time.” In my paintings, the nets create spaces and capture events. The horse saddles are metaphors for the search for harmony between two beings, having an asymmetrical relationship. The sculpture Untitled (stirrups) is made of leather straps and stirrups. The stirrups, designed to maintain balance, are aligned vertically on the straps. They evoke a ladder, the axis mundi, that is, the connection between Heaven and Earth. When I speak of metaphor, I am referring to the idea that the work eludes definition, constantly projecting its form onto an infinite number of other thoughts.

I remember you sharing your thoughts with me when I was working on a project involving the graphic interpretation of music. You told me that between the appearance of a form and its disappearance, there exists a fragile compositional equilibrium. And painting - like music - seeks harmony. How does this quest for harmony, a subject that has long been dear to you, continue to infuse your work? I say “quest”, but perhaps you have found the right melody, the right rhythmic flow and the perfect consonance?

Yes, the word harmony was a recurrent theme. Music provokes instant emotions. I would like my paintings to be listened to and my sculptures to be perceived as a rhythm. This may sound abstract, but at the same time it is concrete in my works. Shapes appear as much as they vanish. I like them to produce a temporal, musical impression, something both anchored and fleeting. In the First Dance and Movement paintings, I searched for a perfect balance between light and darkness, a point of equilibrium between two opposites.

“The ocean is deathless - The island rise and die - Quietly come, quietly go - A silent swaying breath” Agnes Martin

I'm also thinking of Roni Horn, Sigmar Polke and Eva Hesse.

I do indeed remember the Sigmar Polke exhibition at Palazzo Grassi in Venice, which described the artist as “the painter of metaphors”. One of the huge works on show featured circus characters and animals balanced on chairs, buckets and ladders. Polke transforms and even metamorphoses his colors, like an alchemist. How do you work with materials and colors? Do you, like Polke, seek to create - through a singular use of pigments - a state akin to hypnosis?

I began imagining the paintings for the exhibition during a few weeks spent away from my studio. As always in my work process, I need to immerse myself in places, readings, conversations and emotions to prepare a new series. Back in the studio, a blending occurs between my intentions and the interactions that take place between pigments, paint, water, threads and the surface of the canvas. The paintings from the Surface series are made with a single color. I compose the painting by placing water-soaked nets on the canvas. By moving the pigments, the nets modify the pictorial surface, and after they are removed once dry the final painting appears. In this, I am also a kind of alchemist. There are certain colors that come up frequently: the contrast of black and white that structures the nets, the crimson color of bodily flows, of the sea in the Odyssey, of vital momentum. In the painting Suite, the fleeting shape of the net was almost enough on its own. I wanted to add a blue line to indicate temporality and movement. There is also the imprint of a net that traces a very low horizon line. You speak of a state close to hypnosis. What is certain is that I am led by my intuition, by the fluctuations of my memory and by the beauty of the absolute present offered by a painting in the making.

2025

riding stirrups

leather - variable dimensions

untitled (braid)

2024

fishing net - hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 120x90 cm

Low Tide

2024

worn out saddle

horse saddle - variable dimensions

Untitled (worn-out saddles) - I'm Herdsman of a Flock - solo show at Stallmann Galleries - Berlin

https://www.contemporaryartlibrary.org/project/alizee-gazeau-56518

2024

hammock

acrylic and ink in canvas - 190x120 cm

Négatif_1, Suite 2_3, Stallmann Galleries - Berlin

2024

worn out horse saddles

two saddles - variable dimensions

Stallmann Galleries - I’m Herdsman of a Flock - Berlin

Text by Christina-Marie Lümen

Alizée Gazeau presents I’m Herdsman of a Flock at Stallmann, Berlin, an installation of 17 horse saddles mounted in a straight line on a gray wall. The installation is minimalistic, an impression emphasised by the gray colour of the wall alluding to concrete. The strict mounting, sleek leather, and sharp forms create a radicality forcing its presence onto us.

The saddles are presented upside down, with their insides facing the viewer, the flaps outstretched. The variety of positions among the same object recalls sheep of a herd; some are resting, some are fighting, some shy, others showing up.

Gazeau first started working with the saddles in 2020 after finding one at her friend Raoul’s stables in Yvelines. What struck her was the changed nature of the saddle when being turned around; suddenly, it became a flower, a butterfly, a womb.

Transformation is at the core of Gazeau’s artistic practice. In her paintings and sculptures, the artist takes objects of use out of their original position and function, employs them as artistic tool or turns them into puzzling encounters. The imprints of fishing nets become reptile skin and parchment; saddles become sheep, beetles and breasts.

Accordingly, the artist does not aim at representing an object. She wants to reduce the distance to reality, render an object perceivable by taking it out of its ordinary position and use, and opening up the manifold natures of what we think we know. This ability to change perspective, embrace the mysterious, and to subtly but deliberately include a – female – sensuality into her work aligns Gazeau with artists such as Meret Oppenheim or Louise Bourgeois. The process is an evolution from Surrealism, the Objet trouvé and the readymade over Minimalism to a 21st century form. A metamorphosis, giving the factual – concrete, object of use – a poetic touch.

Having completed a double degree in art history and philosophy before dedicating herself to her visual artistic practice, Gazeau finds inspiration in literature and poetry. The title of the exhibition is taken from The Herdsman (1925) by Fernando Pessoa (1988-1935), whose writings deeply influence Gazeau’s work.

I'm herdsman of a flock.

The sheep are my thoughts

And my thoughts are all sensations. I think with my eyes and my ears And my hands and feet

And nostrils and mouth.

To think a flower is to see and smell it. To eat a fruit is to sense its savor.

The poem expresses a shared artistic, and indeed life approach. Commenting on why Gazeau feels such a strong connection to the writer’s work, the artist names Pessoa’s ambiguity between being a grounded realist and utopian dreamer. By reducing the physical to its poetic and sensual existence, Gazeau confronts the essence of things; and she wants us to do so, too.

For Gazeau, I’m Herdsman of a Flock constitutes an artistic statement illustrating in a direct way Gazeau’s perception as an artist: She works with found objects in an intuitive and sensitive way.

In the gallery, the saddles amount to a flock. Stallmann is becoming a stable for the lost sheep of sensation.

2024

greek table cloth

acrylic on jute canvas - 140x100 cm

Eleonas_1

2024

hammock

acrylic and ink on canvas - 190x120 cm

Surface series

2024

fishing nets

acrylic and ink on canvas

Installation Lapis Lazuli:arte

Letters with Liberty Adrien, Catalogue Venezia: Diari d'Acqua

Berlin, Tuesday 16 January 2024

Dear Liberty,

I wanted to tell you about my outing on the Lagoon on 2 October 2023. I met Pietro Consolandi at Piazza Santa Maria Elisabetta on the Lido to take a boat ride. The horizon widened. The Lagoon stretched from barena to barena, and I felt like I was in the heart of an organic archipelago, in the lungs of this whole body that was seeking to reach the ocean. The samphire was red, mingling with heather, and we went along Sant’Erasmo at low tide. I was there, plunged into this thickness of duration that Henri Bergson defines as composed of two parts: our immediate past, and our imminent future. Conscious, therefore, of a memory I had come there to preserve.

Venice, 7 December 2023. In the studio, a series of paintings float, hanging from the mezzanine, made over these past three months in Venice. The paintings are supple, flowing; they flutter as soon as I open the door to go out to the garden. They remind me of a sentence Lisa Robertson wrote in The Baudelaire Fractal, ‘Time in water is pliable’. Time in Venice has unfolded gradually over these past few months, like the current of a stream gradually turning into a torrent. I’m facing the paintings. They are red, purple, pink, wrung from the mesh of the nets I used to paint them. Red is the colour of the pulse of life, and purple, that of the Mediterranean in Homer’s Odyssey, frequently threatening and thus, vinous. The paintings evoke an imminent immersion: they stand like flags, freely, sails enveloping their surfaces like a second skin. The other day, you asked me what part of my work is autobiographical. When I came to Venice, I had the term oceanicity in mind, the degree to which the climate is affected by the influence of the sea. I come from the Atlantic coast, from the French departments of Finistère and Loire-Atlantique. My maternal great-grandfather Ester was an Italian immigrant who worked as a mason. He settled in Brest and married Jeanne, who would become a fabric merchant. My grandmother worked for years with her mother in her fabric shop, Le Dès d’Argent in Brest. We always exchanged a lot about colours, textures, fabric and how to preserve, reinvent, fabricate. Her entire memory has been enshrouded in a thick fog, but just recently, we talked more about colours and did some sewing together. The idea of oceanicity allowed me to question myself about the capacity of streams of memory to spark my creativity and the stories of others, my empathy, like an ocean current. Memory is the imprint of reality on the surface of thought. The imprint, as Georges Didi-Hubermann writes, ‘is firstly a gap that is printed, touching and even ‘impressing’ us, in its distinctive and inaccessible memory of contact’. I think my paintings propose a form of living with change, with the fluctuations of thought. What do you think of the idea of inner landscape?

I’d like to end this letter with another sentence by Lisa Robertson: ‘The distinction between inner and outer worlds was becoming permeable and supple, like a fabric, which is in its very technical constitution both structure and surface’.

Warm regards,

Alizée

Frankfurt, 28 January 2024

Dear Alizée,

‘When they went ashore the animals that took up a land life carried this them a part of the sea in their bodies, a heritage with them passed on to their children and which even today links each land animal with its origin in the ancient sea. Fish, amphibian, and reptile, warm-blooded bird, and mammal – each of us carries in our veins a salty steam in which the elements sodium, potassium and calcium are combined in almost the same proportions as in sea water.’ Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us

In recent days, I have plunged back into Rachel Carson’s book, The Sea Around Us. The first work in a trilogy published in 1951, her words weave together poetry and scientific knowledge in an extraordinary exploration of the ocean’s depths and its history. The writer’s representation of the language of the sea made me think of you, in how your series of paintings could be a fragmentary transposition of this.

The notions of layers, sediments, lights and colours, at the heart of your artistic process and essential components of oceanography, have particular resonance. In her book, Carson explores the ‘vertical migration of the layer’ between surface waters, deep waters and undersea reliefs, ensuring undersea life through ‘a series of delicately adjusted, interlocking relationships’. The verticality and essence of these interactions reflect the ones inherent to your works. The paper spread out on the ground, the fishing net placed upon it, the liquid saturated with colour and minerals enveloping them, and the chemical and physical reactions arising from their interactions – of earth (gravity), air (evaporation) and light (colour change) –form your paintings. Once the water has evaporated, leaving behind its deposits in the nooks of the net, which has been carefully removed, a map of traces and processes remains, a representation of reliefs and histories. ‘The sediments are a sort of epic poem of the earth’, Carson writes. Their nature and their arrangement recount the history of the seas and oceans – they are the imprint of relationships.

In your letter, you touch on associations and attributions of colours, relating to your body of work, your biography and your perception of landscapes. These complex interactions between visual and sensorial impressions influence our ever-changing reception of the colours of the seas and oceans. Our vision is affected by the presence of living bodies, microorganisms, molecules and reliefs, as well as by sunlight, heat, time of day and season. Our senses are stimulated by the emergence of memories, places and moments experienced or known, prompted by this contemplation.

The evocation of your personal and familial ties to Finistère, and your interest for the notion of inner landscape, brought to my mind the North Sea coast, in northern France, where I spent much of my childhood. Its landscape has been shaped by two powerful forces: that of strong tides and ruins from History. Every day, the sea, subjected to the pull of the moon and sun, withdraws, sometimes kilometres, revealing a perpetually changing topography of sand. Its windswept dunes, standing opposite the ‘vast world of sea and sky’, as Carson writes, are marked by the spectral, imposing presence of blockhouses. These concrete buildings, attesting to the German army’s occupation during World War II, hold an immense sense of desolation and violence. They’re slowly sinking into the sandy ground, as though the earth were swallowing them up. The striking forces of the natural world here seem to confront Humanity’s fragility. This was my first reception of deep emotions emanating from a landscape. I’ve gone over wordcount, and the hour is late, so I’ll end my letter with a request: I’m curious to know more about your relationship with the notion of Oceanicity.

Looking forward to hearing back from you soon.

Warmest,

Liberty

2024

glass float

glass float - fabric

untitled (glass float)_2

2023

fishing nets

acrylic and ink on canvas - 300x190 cm

Haütung - Gr_und - with the support of the French Institute - Berlin

AN END TO A SENTENCE - a conversation between Alizée Gazeau and Lisa Deml

Lisa Deml: The impression that settled on my mind when I first came to see this series of painting in your studio was that of maturity. To me, these paintings are a very clear and condensed expression of different lines of thought and experimentation that you have been following for several years. They seem to have grown through practice and now coincide with your first solo exhibition. How is this exhibition situated in your artistic development, what does it mean to mark this point in time?

Alizée Gazeau: I consider this exhibition as an opportunity to end a first sentence. I invoke the notion of a sentence, but you could also say it marks the end of a first journey. My work is concerned with process itself and I have the feeling that I could develop the same idea further indefinitely. In this sense, the exhibition at gr_und is also a challenge for me to put an end to this process. Even though I would never say that this process is finished, I have reached a point when I can let it settle down and let go. When the work enters into an exhibition space, it does not belong to me anymore, it is not about me anymore—the work has to speak for itself, as Louise Bourgeois would insist. She says that an artwork has nothing to do with the artist; it has to stand for itself. I find this credo helpful to navigate the tension between the intimacy inherent in artworks and the extrovert nature of exhibitions.

This is not only your first solo exhibition but also the first time that you work in painting and to this scale. How did you arrive at this discipline and format of 200 x 300 cm? Would you say that it is the result of a measure of trust and confidence you have gained in the process?

I felt the need to not only engage the hand and the eye in the work process but to involve the whole body. It is a very physical process as I work on the floor and pull and place the hammock and the net on the canvas. And it is not only a physical experience for me in the production process but also for the viewer in front of the paintings. I wanted the paintings to be bigger than us, so that they create an immersive sensation that exceeds the human body.

Given the expansive format of these paintings, how do you approach the canvas to begin with?

The paintings make me as much as I make them. It is a conversation between me and the various materials involved in the process, the canvas, the net, the hammock, colour and water. With these components, I create an environment, a framework within which the painting can emerge. Of course, the work process is different with every painting, there are different layers and rhythms at play each time. But what characterises my process is that I organise a situation on canvas and then leave the studio while the painting takes form. I return to it when everything has dried and I can remove the hammock and net to discover how they have impressed themselves on the surface. I very much enjoy this moment of revelation because it is often surprising. It is almost like a laboratory where I arrange the experimental setup and observe how it develops on its own. It is a delicate balance between controlling and letting go. While the first part of the work process is determined by my decisions and choices, the second part is beyond my command. So, even though this series of works are undeniably paintings, I would not call myself a painter.

What I find remarkable about your artistic practice is that all the components and materials that are involved in the production process retain a certain degree of agency and autonomy. This becomes most pronounced in the way in which you interact with the surface of the canvas. I know that you have given much thought to the notion of the surface—could you talk about what the surface is to you?

Of course, factually, paintings are two-dimensional, they have a flat surface. But I try to expand this understanding and to experiment with a sense of depth in my paintings. I want to create a sensation of the paintings coming towards you as you face them and dive into them. To me, this is also a reflection on what it takes to be an artist. At some point, I questioned myself and whether I am ready to be an artist or not. And an answer to this question is related to being ready to dive, to venture beyond the surface, and to confront memories and feelings of doubt and darkness. Producing these paintings was an almost physical experience of diving in and resurfacing to catch my breath. I think of these paintings as permeable surfaces. In a metaphorical way, they are questioning the idea of the skin, which is exposing you to the world at the same time as it is protecting you from it. To some extent, producing and showing paintings could be considered a healing process, not only for the artist but also for the people seeing them, as an instance of taking care.

As you mentioned the idea of the skin, this takes us to the title of the exhibition —Häutung. This notion of skinning seems to resonate on so many levels with your artistic practice, with the paintings themselves and their aesthetic impression, as well as with your work process and development as an artist. How do you relate the idea of Häutung to your practice?

As my work is concerned with the process itself, it is strongly connected to the concept of metamorphosis. For me, the process of printing relates to a continuous struggle to come to terms with the perpetual evolution and movement in which we are all implicated. Printing or imprinting are ancestral practices, ways to experience or own existence, for instance through handprints in stone or fossils. I had already produced prints with different found objects from the environment when I found the fishing net. It reminded me of fish skin itself—an interesting paradox, that the net mimics that which it is supposed to catch. The hammock is also a curious object that is allowing us to lie down and rest in nature, precisely by protecting us from the natural ground. Eventually, I moved away from natural elements towards tools that humans produced in order to enter into a conversation with what is called “nature”. In many ways, this is very similar to artistic practice, and to my artistic practice in particular. Both the hammock and the net are permeable and ambivalent between controlling or letting go. And once I have printed them on canvas, they become something else altogether and take on a second life.

The paintings offer a very immersive experience. Initially, I thought of them as cartographies but, rather than looking onto a landscape from above, they seem to draw one into the landscape, into a submerged perspective. Agnes Martin once said that, to her, painting was like going into the field of vision, as you would cross an empty beach to look at the ocean. I consider this to be a very fitting description of these paintings, an invitation to look beyond them.

This is one of my favourite quotes of Agnes Martin and it resonates strongly with me. Of course, the paintings have a physicality and presence but I hope that they, in a way, disappear behind themselves. Each painting holds a space that not only unfolds spatially but also temporally. Perhaps it is for this reason that I always work in series, to express a certain rhythm, a perpetual movement or evolution. While each painting is a work in and of itself, it is also part of a larger whole, of a score or sentence. In the exhibition at gr_und, I will continuously change the composition and chronology of the paintings so that the viewing experience will be different at every visit to the gallery. In this respect, my curatorial approach correlates with my artistic practice as they are both concerned with the process itself and with keeping this process alive. This might come out of a fear of completion and stasis, but I want to think of it as an openness towards fluidity. To me, fluidity is a good word to indicate a method of working rooted in humility, in acceptance of incompleteness, and a sense of reverence for the material at hand, for the unfolding process, for the shared space, and for the other artists and their work. Fluidity as a working method is especially important in collaborative projects, and the experience of curating the group show Off Water was exemplary in this respect. It felt very rewarding to work with all these artists, all women artists, I should say.

As I understand it, the notion of fluidity that you suggest is correlated with a tendency towards permeability. Would you agree?

Certainly. However, it is not only a poetic concept but born out of necessity, too. Over the last few years, as I have been developing my working method, I realised that it is impossible for me to control the entire production process. I had to allow myself, after setting the framework for production in the studio and performing my part, to give in to the process and leave the painting as it was taking form. This is where my sense of humility and reverence for the material and process comes from and, at the same time, where I arrived at a form of liberation or emancipation in my working method. I freed myself from any expectations I might have had towards the working method and developed a production process that most closely aligns with my perception of these paintings. For the first time, I feel that the way I am working corresponds with the ideas I am thinking through. And perhaps this is where the impression of maturity arises that you mentioned at the beginning.

In the exhibition at gr_und, you not only present this series of largescale paintings but also two sculptures and a textile work that you bring together in a material assemblage. In contrast to the paintings in whose expansiveness one can get lost, these sculptural pieces are very condensed and highly plastic.

In fact, the two sculptures are saddles that I found at a stable. Similar to the fishing net and the hammock, the saddle is a tool produced by humans in order to communicate with nature. The saddles were lying upside down on the floor of the stable and I was surprised to find that they looked like flowers or vulvas. Even though the common notion of horse riding and the dimension of power and control associated with it are rather masculine, when turned upside down I found the saddles to be very feminine objects. I was intrigued by how the quality and meaning of an object could be shifted simply by looking at it from a different perspective. The same shift happens when an object enters an art space where the saddles are now installed on a wall as art pieces. Strictly speaking, they are not sculptures because I did not produce them but they become sculptural through their exhibition. And I present them in an assemblage with a piece of fabric that I found on the street when I first moved to Berlin. I cut it in rhombus-shaped pieces echoing the pattern of the fishing net and the hammock and sowed it back together. The rhombus is a symbol for femininity in many cultures as well as the basic form of a mandorla which is used in Christian iconography to frame religious figures. As part of the exhibition, the fabric with its rhombic pattern might be associated with a cocoon or discarded skin. But it is very important for me that each piece in the exhibition is open to manifold interpretations and invokes different associations that are all valid.

I cannot help but think of Louise Bourgeois again, not only her insistence on the autonomy of the artwork in interpretation but also her process of doing, undoing, and redoing that you have just described. The fact that this work of doing, undoing, and redoing is never done, that there is never a moment of completion—does that not feel exhausting?

It is exhausting and yet essential that there is something that remains unresolved and that drives the process onward through continuous questions. To evoke Agnes Martin’s words again, she defines the artist as someone who wants to quit everyday but continues anyway. It is exhausting at the same time as it is healing. There are these moments when I return to the studio and remove the nets from the painting to see how it has taken form—and to find that something has happened that resembles an answer or an end to a sentence.

2022

fishing net

acrylic on canvas - 300x190 cm

H_22_1 & H_22_2

2018

olive tree branches

Drawings on paper - 20x30 cm

Olea Europaea - during a residency at the Hartung Bergman Foundation, France